Burning Man

by Lee Gilmore

Every summer, tens of thousands of experience seekers from around the world descend upon a desolate and otherwise obscure corner of northwestern Nevada known as the Black Rock Desert. This utterly empty expanse of dried alkali clay—known as the playa—is transformed into a pulsating cultural laboratory in which participants—known as Burners—deliberately experiment with art, symbol, ritual, and community.

Burning Man presents a restive nexus of complex spiritual narratives. Participants in this extravagant and kaleidoscopic festival have created a theater in the barren desert in which to play reflexively with culture. This pageant of artistry and ritual performance presents a captivating paradox of decadence and ostentation that is simultaneously a studied testament to impermanence and flux. Participant narratives highlight themes of self-expression, personal transformation, communal bonding, and cultural renewal, and many describe Burning Man as providing a sense of “spirituality,” while explicitly disclaiming that the event is “religious.” For their part, the event’s founders and organizers likewise hope that the event will “produce positive spiritual change in the world,” even while they also stop short of characterizing the event as a “religion.” But Burning Man is perhaps less about spirituality—intangible and ineffable—and more about the immediacy of ritual. The hybrid ritualism of Burning Man challenges normative assumptions about the location of lived religious practice and spiritual expression, and points to challenging questions about the tensions between these constructs.

Burning Man started as a small impromptu gathering among a handful of friends on a San Francisco beach in 1986 who would eventually move the event to the desert in 1990 where it grew steadily into a globally renowned phenomenon drawing around 50,000 participants annually. Dubbed “Black Rock City,” this encampment temporarily becomes Nevada’s fifth largest metropolis, complete with roads, street signs, peacekeepers, medical services, and a downtown coffee house. However, the infrastructure remains minimal and requires that all attendees bring everything they need to survive—including all food, water, and shelter—in an extremely dry and harsh physical environment. Daily temperatures can range from the low 40s overnight to well over 100 degrees, and winds can exceed 75 miles per hour, occasionally fomenting intense dust storms and white-out conditions.

At the center of Black Rock City stands the towering wooden icon of the Burning Man. Crisply lit with multicolored shafts of neon and ultimately packed with fireworks and other incendiaries, this ostensibly genderless sculpture stands over the city at once helpless and defiant against the dusty night sky, awaiting its climactic detonation. Arrayed around this axial and enigmatic effigy are hundreds of other works of art created by festival participants. Often constructed on colossal scales, these artists—both professional and amateur—go to great length and expense to create and transport these works to the desert. And at the festival’s conclusion, the entire city is completely dismantled and removed until the following year, such that within a month’s time no trace of the event remains on the playa’s surface.

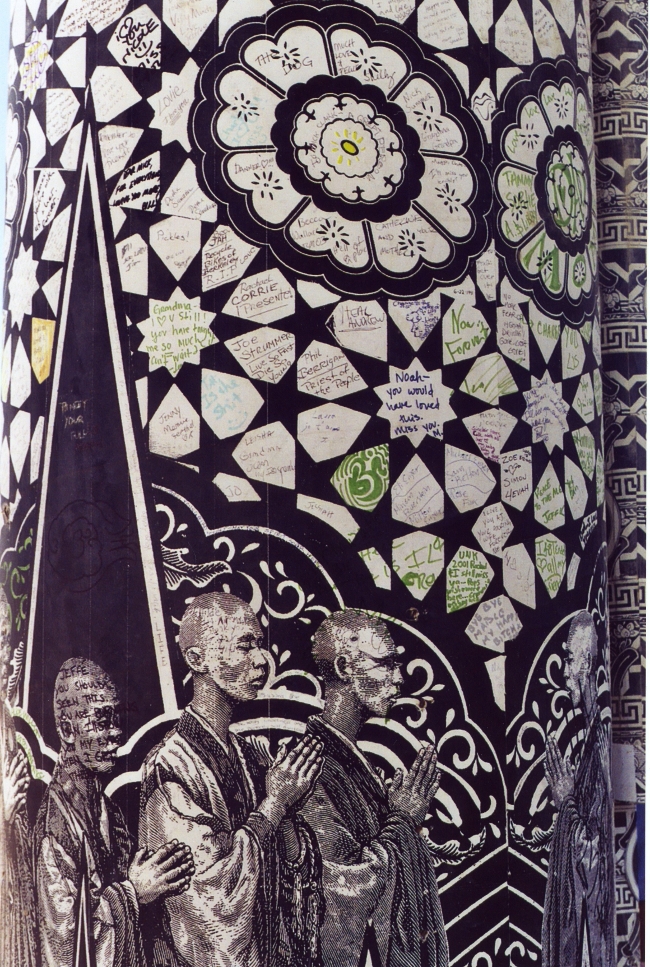

This hyper-spectacle generates an energetic and continuous flow between chaos and order. Concepts and symbols originating within diverse cultural and religious traditions are playfully and creatively converged, forging ritualistic pathways towards catharsis, ecstasy, and insight. In addition to the definitive ritual bonfire, numerous other rites—both sincere and satirical—have transpired here: massive ephemeral temples dedicated to memory and mourning; anti-consumerist parodies of Christian evangelism; operatic performances invoking Vodou lwas; Shabbat services conducted in the skeleton of a gothic cathedral; reiki attunement sessions; labyrinths; yoga, meditation and kabballah classes—the list could go on and on. At Burning Man, the random flotsam of human history and global cultures washes up on the shores of the Black Rock playa for one week, and then washes back out as participants return to what they call the “default world,” having shared in an experience that often leaves residual traces on their sense of self and notions of culture. Burning Man renders the native hybridity and plasticity of cultures transparent, revealing the extent to which religions are not static, historically bound institutions, but rather lived, fluid constructions. Syncretism and bricolage are nothing new in the history of religions as the defining and transgressing of boundaries seems definitional to community. While conservative traditionalists tend to see such mongrel developments rather unfavorably, history shows that whenever diverse cultures and religions come into contact they inevitably adopt ideas, symbols, and performative modes from one another, while also retaining or rejecting other core elements—a process of retrenchment that is itself a dynamic response to change.

At Burning Man, embodiment and experience are emphasized over doctrine or ideology. For example, Burning Man’s founder and ongoing chief visionary, Larry Harvey, speaks of “immediacy” as akin to a sacred power, writing that through immediate experience “We seek to overcome barriers that stand between us and a recognition of our inner selves, the reality of those around us, participation in society, and contact with a natural world exceeding human powers.” In the beauty and essential simplicity of the Black Rock Desert—as well as in the visceral experience of its arid and demanding environment—Burners often report a transformative sense of the numinous. The desert evokes a potent mix of limitlessness and mystery, as well as time-honored themes of hardship and sacrifice that are deeply embedded in the Western cultural psyche. This juxtaposition between the vast, vacant landscape and human, artistic abundance fosters unique perceptions of space and time, both embodied and imaginal. Participants also frequently speak of community, self-expression, and self-reliance—echoing a set of ethical principles articulated by the event’s organizers—as interrelated themes. These dynamic encounters between self and other—in tandem with embodied experiences of the desert—coalesce to generate critical transformations for many participants, leading some to ascribe spiritual significance to this event.

For Burners, spirituality is fundamentally experiential (based on the primacy of personal experience and personal authority in framing those experiences), reflexive (inspiring reflections on self, self/other, self/nature, and self/culture), and heterodoxic (constituted by multiply-layered, fluid, and non-centralized constructions of meaning). But troubling any simplistic conclusions, many other participants state most emphatically that Burning Man does not entail any sense of spirituality—even while some of these same individuals also engage in expressive, ritualized quests for self-discovery through the event, but which they elect not to cloak in mystical terms. Furthermore, some observers and participants alike deny that this festival has any redeeming qualities whatsoever, seeing it as merely an excuse for debauchery and a license for transgressive behavior that is disconnected from any overt spirituality. Yet while the event is undeniably rife with opportunities for hedonistic indulgence, it would be mistaken to understand hedonism as anti-religious. Dismissals of Burners as pleasure-seekers reveal the deep and lasting imprint of America’s ascetic Protestantism. Furthermore, religious traditions that are utterly bereft of some opportunity for joyous, and occasionally excessive, celebration as part of the package deal are comparatively rare.

Competing perspectives are the engine that drives Burning Man, as it is through an ongoing and idiosyncratic process of argument and dissent that participants define, refine, and perform their collective notions of what this event is all about. Burning Man sits at the vanguard of contemporary anxieties around meaning, identity and experience that resist easy classification. People increasingly seek after eclectic, hybrid, dynamic, and reflexive spiritualities that whisper of deep and direct connections to an elusive “more,” while conceptually positioning these quests outside the rubrics of what they understand to be “religion.” But to say that Burning Man is “spiritual” or “spiritual but not religious,” only goes so far. Burning Man speaks to the persistence and importance of ritual as a vehicle through which humans connect with one another and as well as with that mysterious “more”—an ineffable sense of something larger than ourselves—while also showing us how these expressions seep beyond the comfortable bounds of both academic and popular concepts of either “religion” or “spirituality.”