Every summer, tens of thousands of experience seekers from around the world descend upon a desolate and otherwise obscure corner of northwestern Nevada known as the Black Rock Desert. This utterly empty expanse of dried alkali clay—known as the playa—is transformed into a pulsating cultural laboratory in which participants—known as Burners—deliberately experiment with art, symbol, ritual, and community.

Burning Man presents a restive nexus of complex spiritual narratives. Participants in this extravagant and kaleidoscopic festival have created a theater in the barren desert in which to play reflexively with culture. This pageant of artistry and ritual performance presents a captivating paradox of decadence and ostentation that is simultaneously a studied testament to impermanence and flux. Participant narratives highlight themes of self-expression, personal transformation, communal bonding, and cultural renewal, and many describe Burning Man as providing a sense of “spirituality,” while explicitly disclaiming that the event is “religious.” For their part, the event’s founders and organizers likewise hope that the event will “produce positive spiritual change in the world,” even while they also stop short of characterizing the event as a “religion.” But Burning Man is perhaps less about spirituality—intangible and ineffable—and more about the immediacy of ritual. The hybrid ritualism of Burning Man challenges normative assumptions about the location of lived religious practice and spiritual expression, and points to challenging questions about the tensions between these constructs.

Burning Man started as a small impromptu gathering among a handful of friends on a San Francisco beach in 1986 who would eventually move the event to the desert in 1990 where it grew steadily into a globally renowned phenomenon drawing around 50,000 participants annually. Dubbed “Black Rock City,” this encampment temporarily becomes Nevada’s fifth largest metropolis, complete with roads, street signs, peacekeepers, medical services, and a downtown coffee house. However, the infrastructure remains minimal and requires that all attendees bring everything they need to survive—including all food, water, and shelter—in an extremely dry and harsh physical environment. Daily temperatures can range from the low 40s overnight to well over 100 degrees, and winds can exceed 75 miles per hour, occasionally fomenting intense dust storms and white-out conditions.

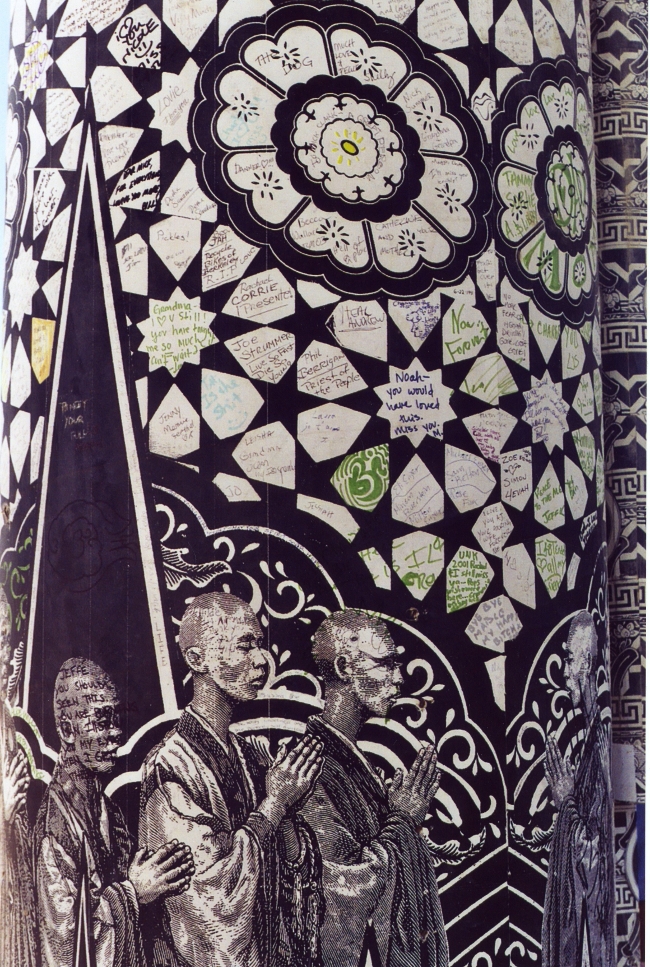

At the center of Black Rock City stands the towering wooden icon of the Burning Man. Crisply lit with multicolored shafts of neon and ultimately packed with fireworks and other incendiaries, this ostensibly genderless sculpture stands over the city at once helpless and defiant against the dusty night sky, awaiting its climactic detonation. Arrayed around this axial and enigmatic effigy are hundreds of other works of art created by festival participants. Often constructed on colossal scales, these artists—both professional and amateur—go to great length and expense to create and transport these works to the desert. And at the festival’s conclusion, the entire city is completely dismantled and removed until the following year, such that within a month’s time no trace of the event remains on the playa’s surface.

Page 1 of 3 | Next page