At first there is no time.

That is what I tell myself when I am asked for my views on a topic that is spiritual.

There is a white page and that is like a box. I have to write in it. Literally, it is a box of light I have to darken. I have to fill it to some extent.

But, of course, there is no time. So I don’t write.

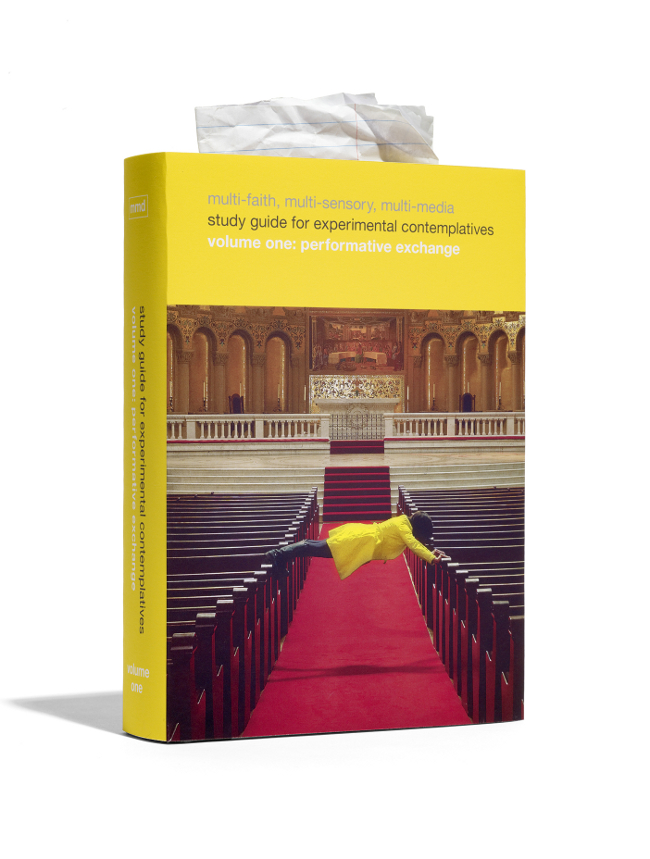

The contemplation of a box, or boxes, can become a spiritual event. Joseph Cornell approached boxes like that. (Or did he?) Very organized people do this, too. The results are more mundane. Still, there are entire stores devoted to it, towers of gleaming cabinets, geometrical temples that shine. Compression, the aesthetics of stacking and order. It is nice.

Collectors do this. They put things in boxes, and thus capture a moment in the physical world. The thing in the box is frozen. The thing in the box stops time.

(Aside. Transparency is essential to this experience. If light cannot pass through the box, game off, we might as well be blind.)

Is that what God looks like? A butterfly? A marble? A tiny Victorian chair?

Why, the answer is certainly, Yes.

I should write that, too, but I don’t.

Months pass, and I don’t—write, I mean. I fill that no-time with activities that consume time voraciously. They are of two sorts. The first sort involves me meeting the demands of productivity in time, as defined by others. I strive to accomplish a certain number of things to the satisfaction of others and myself in a certain time frame. Often I fail. I go outside the frame. Or I never make it in. I’m not sure.

The second sort are of more interest to me. These involve me obliterating the imposed structures of time and space. It’s 6:45 p.m., people, in Times Square. I have just walked out of one box and I am not about to descend into another.

I am itching to bust out of the temporal. Altered perceptions of or manipulations of sound and light, intensifying the hum in the wiring. I strive to do this without hurting anyone. At times there is tempo, but it is distant, barely perceptible. As sometimes you can hear your pulse, muffled, beating in your temples and ears. Sometimes there is alcohol. Chemical changes brought on by sexual arousal. Smoke. Or sunlight.

The requests for my views are persistent, gently and kindly so. Because I am instinctively drawn to activities that deliver me an illusion, a vision even, of self-worth, I cannot refuse. I want to do what I’ve been asked to do.

I am supposed to know about these things. But I don’t. I am immersed in the daily lives of philosophers, musicians, poets, children. Yet it is clear that I do not know what “spiritual” means. I begin to believe the idea is an illusion. A fucking fraud. And I love that.

Over time, I agitate more and more, but something in me can’t let the idea of it go. I begin talking out loud, dissociatively, to my wife. In bed most nights I say to her, “I’m going to do that thing I told you about.” And she says, “Good.” But of course, I never do.

In my mind I compose a piece about how the only people who can consistently communicate a sense of the spiritual to me are artists—specifically, the masters of abstraction whose acknowledgement of the concrete, temporal world is certain, but implied. Their inventions may celebrate or reject that physical world: they compress, reshape or expand our sense of space and time. And thus we experience it anew. As though perhaps we are breathing air for the first time, or warming in the sun.

The piece centers on the work of the composer Morton Feldman, who created an entire realm of music I can only call celestial, partly by shunning the typical notions of time. Feldman’s music, even when written out and measured, cannot really be said to progress. The experience of it is this. At one moment the music does not exist, yet in another moment it does. And it may ring harmonically in your ears. It may shock or grate. But it does not seem to go forward or backward. It expands. It sounds.

I think of Durations, of Crippled Symmetry, of Rothko Chapel, and of Coptic Light.

In many ways, Feldman replaced Jesus for me. He appeared to be as unspiritual a creature as one could imagine. He was fat. He chain-smoked unfiltered cigarettes. He spoke with an absurdly thick New York accent, the sort that you’d think they only invented for movies of the 1930s. But it is with him that I leave earth. And it is with him that I dance, and stop time.

But I didn’t write that either. I didn’t want to put my God in a box. More honestly: I did want to, but I couldn’t.

Page 1 of 2 | Next page