The Apotheosis of Pittsburgh

by Jonathan Schorsch

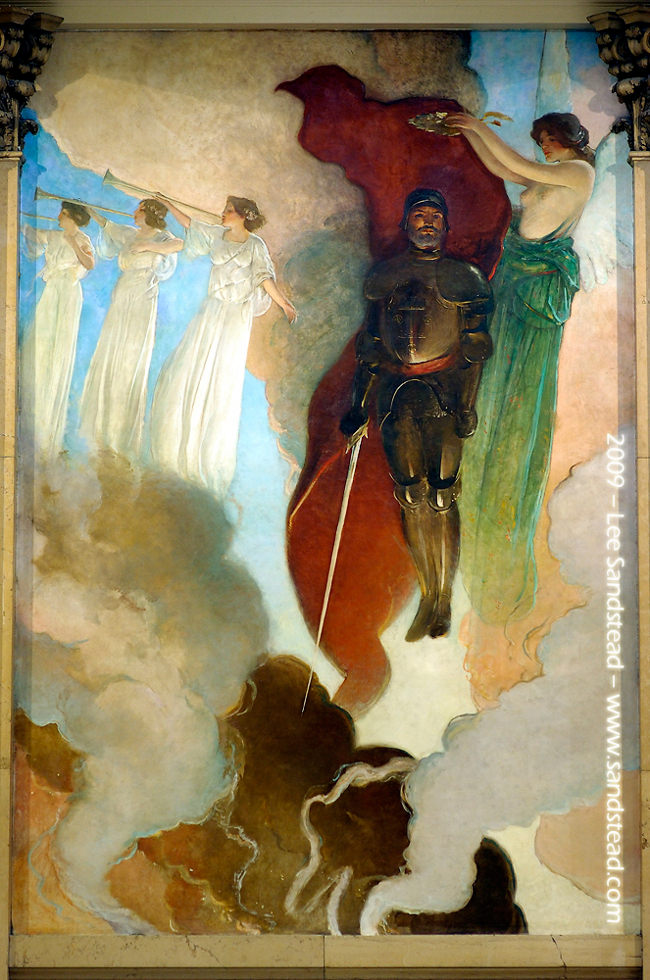

Sanctifying those who govern, harnessing official religion for state ends, inspiring the people, channeling their dreams—even in modernity angels adorn public structures and monuments, whether in victory pillars, war memorials, or paintings of the apotheosis or heavenly ascension of great leaders. The Apotheosis of Pittsburgh, by the then-renowned American artist John White Alexander, is a series of 48 murals, all painted by Alexander between 1905 and 1915, in the grand staircase of the Carnegie Institute (now the Carnegie Art Museum) in Pittsburgh, a cultural haven sponsored by industrialist Andrew Carnegie, dedicated in 1895. Alexander died in 1915, leaving his enormous mural cycle unfinished. The paintings tell and glorify the story of the building of Pittsburgh through the kinds of industries that Carnegie ran and that made him wealthy enough to found institutions for the people devoted to culture and the arts. In the 2nd-story painting known also as The Crowning of Pittsburgh, a knight in black armor floats heavenward, to the sounding of trumpets, about to be crowned with a wreath by angels, the man who made all this bounding development possible, the hero. The knight is meant to be a virile personification of the city of steel and looks quite similar to the Institute’s benefactor, Andrew Carnegie.

Alexander meant his monumental artistic feat to instill in viewers a historical yet mythological narrative that made American industrial capitalism a manner of fulfilling God’s purpose. I came across images of Alexander’s angels while researching a forthcoming book on angels and modernity. As with so many modern angels, I find these riveting. Despite the supposedly anti-metaphysical bent of modernity, the art of public spaces continues to aspire to shape people’s spiritual dreams. Hence one explanation for the continued ubiquity of angels.

Around the ascending knight/Carnegie, around across some of the walls of this enormous “grand staircase” flits a bevy of gorgeous angels, slim, vanilla pure and elongated, an art-nouveau-like chorus line, adoring fans, coming forward with gifts. Their garb resembles fancy evening dresses, their faces and expressions not un-innocent. A few of the winged beauties in the foreground—therefore the largest, most prominent, also highlighted because unlike others they wear colored outfits—are topless, their breasts detailed in a way rather risqué for the angelological tradition. This makes an interesting choice for Alexander, whose many portraits of (human) women, though dwelling attentively on femininity and sensual detail, never depict anything immodest. The figures in The Apotheosis of Pittsburgh are not technically angels. Because the painting hails from a classical genre (apotheosis), they are actually winged genies from classical mythology, not Judeo-Christian angels. The different winged beings from different cultures have a history of coming together and interbreeding, however. Most of the artistically-aspiring viewers of Alexander’s paintings would have understandably seen these winged females as angels. The rising black knight, the modernity of all of the scenes of the building of Pittsburgh serve to Christianize the cycle and essentially make these attractive fairies into angels.

By the time Alexander won this assignment he was an accomplished and internationally admired artist, sought after as a portraitist. An orphan, his artistic life had begun in the Illustrations Department of Harper’s Brothers, publishers of Harper’s, and turned into an American dream. With only this brief experience, and a bit of saved money, he set out for artistic training on a European tour, joined up with continental artists, and remained throughout his life intensely active and successful in painting’s institutional world, becoming an ardent missionary for and defender of American painting. Friend of modernists as varied as Auguste Rodin, Stéphane Mallarmé, Oscar Wilde, and Henry James, considered a great American painter like Edwin Abbey, John Singer Sargent, and James Whistler, from 1909 until his death in 1915 he presided over the U.S. National Academy of Design. As an artist, Alexander came to favor Beaux-Arts, art for art’s sake and the ornamental; fluid lines and soft colors, yet sober; naturalism, but idealized. Rarely did he abandon realism in his depictions.

Born in Allegheny City in 1856, later absorbed into Pittsburgh, a sense of local patriotism likely moved Alexander when engaged in the Apotheosis murals. His own American rags-to-respectability and financial security paralleled that of steel-built Pittsburgh and the nation as a whole, each a fulfillment of the promise of America, it’s manifest destiny, built on grit and faith, at least in the telling of works of art like this. Industrial progress and economic growth is the civil religion Alexander lauds in his imperial-sized painting cycle. By the time he received the Carnegie commission he had painted some official monumental art, such as panels for the Congressional Library in Washington, DC, and had been invited to paint a series celebrating Pennsylvania history for the State Capitol in Harrisburg.

Some monomaniacal drive leads an artist to attempt, much less execute, a work consisting of tens of gigantic paintings. (The original commission conceived of 69 individual works.) The grandiose scale of the physical effort, not to mention the work itself, mirrors the life of the sponsoring institution’s founder and funder, Andrew Carnegie, who made his vast wealth as a canny and ruthless industrialist. Carnegie first laid out his doctrine of social Darwinism and redemptive philanthropy in an 1889 article entitled simply and aptly, “Wealth,” later published in 1900 as part of his book The Gospel of Wealth. Cultural centers such as the Carnegie Institute were to serve as the temples of the new social gospel that sought to improve the lives and souls of the laboring masses. Behind Carnegie and Alexander stands the all-consuming drive toward power, control, reputation and empire critiqued in Melville’s contemporary tragic anti-hero Ahab.

In an update on an age-old motíf, Alexander’s self-exposing and gift-bearing angels comprise the (male) hero’s true gift, his reward for performing well, like a man, for leading heroically. Labor entails one of the main themes of Alexander’s Apotheosis murals—he called the whole cycle “The Crowning of Labor”—and a noticeable gender division distinguishes the masculine exertions that built the city from the heavenly compensation of feminine charms bestowed on the male hero(s). The lower level of murals portray the city’s working classes, a theme that was rare at the time, their lives and labor romanticized for art patrons’ consumption, though Alexander’s depiction of “the laboring male body as physically vigorous and autonomous” obscured “the extent to which mechanization had degraded the role of the skilled worker to that of machine operator.” Here panels named “Fire” and “Toil,” the foundation of Pittsburgh and of Alexander’s paintings, evoke materialism as emerging from hellish conditions. The top level, unfinished when Alexander died, was to show the masses closing in on their goal: culture and the arts, achieved by means of the wealth produced by industry. In between, smoke rises from all the industry, forming into clouds on which flit the jarringly erotic angels as well as the knight in black armor floating heavenward. The knight, personification of Pittsburgh, makes Andrew Carnegie, a robber-baron of the utmost wealth, a self-made public intellectual and quasi-celebrity, into the protector and patron of the people he believed himself to be. Sarah Moore reads the depiction of Carnegie—“aloof and sanguine”—as a reflection of his “practice of absentee corporate capitalism” that featured “[i]ncreased mechanization, a transfer of workplace control from skilled workers to management, and a hiring boom for unskilled and semi-skilled labor” and “a rigid hierarchical line of control.”

Moore considers Alexander’s use of medieval tropes—knighthood, chivalry, and one could add the apotheosis theme itself—as part and parcel of the era’s anxious reaction to the power and wonder but also the dislocations of advancing technology, industry and science, modernity. In different ways spiritualized Christianity both resisted and sanctified technology and science. The angels stand in relation to industry in the paintings much in the way Alexander’s own artistic pursuit of beauty was described after his death by John Agar President of the National Arts Club: “We have had little time in this country to devote to the production of beauty or to the study of its forms. We have had to devise and develop a political government, conquer a wilderness, fashion the commerce and industry of a throbbing nation in a vast continent. Our best minds have been too much occupied with these immediate works to find time for the larger spiritual endeavor.” Like Alexander, Agar genders beauty and spiritual endeavors as feminine, ancillary and supplementary to the more primary masculine work of conquest and building.

As was common in European modernism at the time, Alexander’s bevy of angels represent pure feminine beauty, as well as spiritual beauty; beauty as spirit/mind, spirit/mind as beauty. It should be noted that Alexander apparently initiated an evening class for women at the National Academy of Design. He also co-authored an article in 1910 that, typical for the times, warned against the increasing masculinization of women and effeminacy of men. Perhaps he intended his (unprecedented for him) breast-baring women to remind viewers of the femininity that was proper for women. The beauty and sensuality of Alexander’s angels—certainly manifesting “the vitality of a young and vigorous race” of the figures in his painting in general–the quiet seductiveness of the color and lighting aim to heighten the viewer’s response, and thus double the libidinal energies that must be invested in the heroic accumulation of wealth, the wealth that permits the flourishing of society and great art, which lauds the wealth that made it possible. Sarah Moore says that the winged spirits represent “the arts, music, literature, science, and poetry.” Masculine lust for achievement is rewarded through pleasure in/of the feminine. Viewers could be forgiven for confusion about the carnal rewards seemingly implied by these seemingly Christian angels.

The urge toward beauty that is said to motivate biological reproduction Alexander harnesses to invigorate the cultural reproduction of citizens who believe that they should aspire to Enlightenment/spiritual notions of self-fulfillment: autonomy, reasonableness, civility, refinement. Such citizens are to believe, like Alexander, that the ability to achieve personal wealth unencumbered is justified (in the theological sense), even if by means of crushing, within the limits of the law or beyond, the human aspirations to livelihood, health, and autonomy of others. In this telling, the desire that feeds robber-baron industrial capitalism stems from great (divinely-ordained) desire, great both quantitatively and qualitatively. Beauty, art and culture, properly channeled forms of desire, can improve and redeem the working classes—only Carnegie’s knight gets the heavenly girls, as it were—whose working conditions have been eroded through Carnegie’s and other robber-baron union-busting tactics, can erase or compensate for the harms caused in the very process of producing civilization. Paid for by the libidinal hero, high art intends to sublimate, to spiritualize the libidinal hero and his achievements, the latter beneficently (sycophantically, really) equated to the achievements of the people. On the one hand, suggest Alexander’s topless “angels,” perhaps the joke is on high art. The visual metaphor of spirit subverts itself, leaving only carnal figures, the very sign that, despite art’s intentions, best generates the kind of urges capitalism needs in order to succeed. On the other hand, high art, domesticated by patronage, gets to play its joke as well. After all, it has already been well paid. For our part, we continue to take in (to be taken in by?) art’s mythification of the manufactured toils and travails of the working masses, its mythification of our own worlds. We continue to be shaped by painted angels, larger than life, intended to shape us.