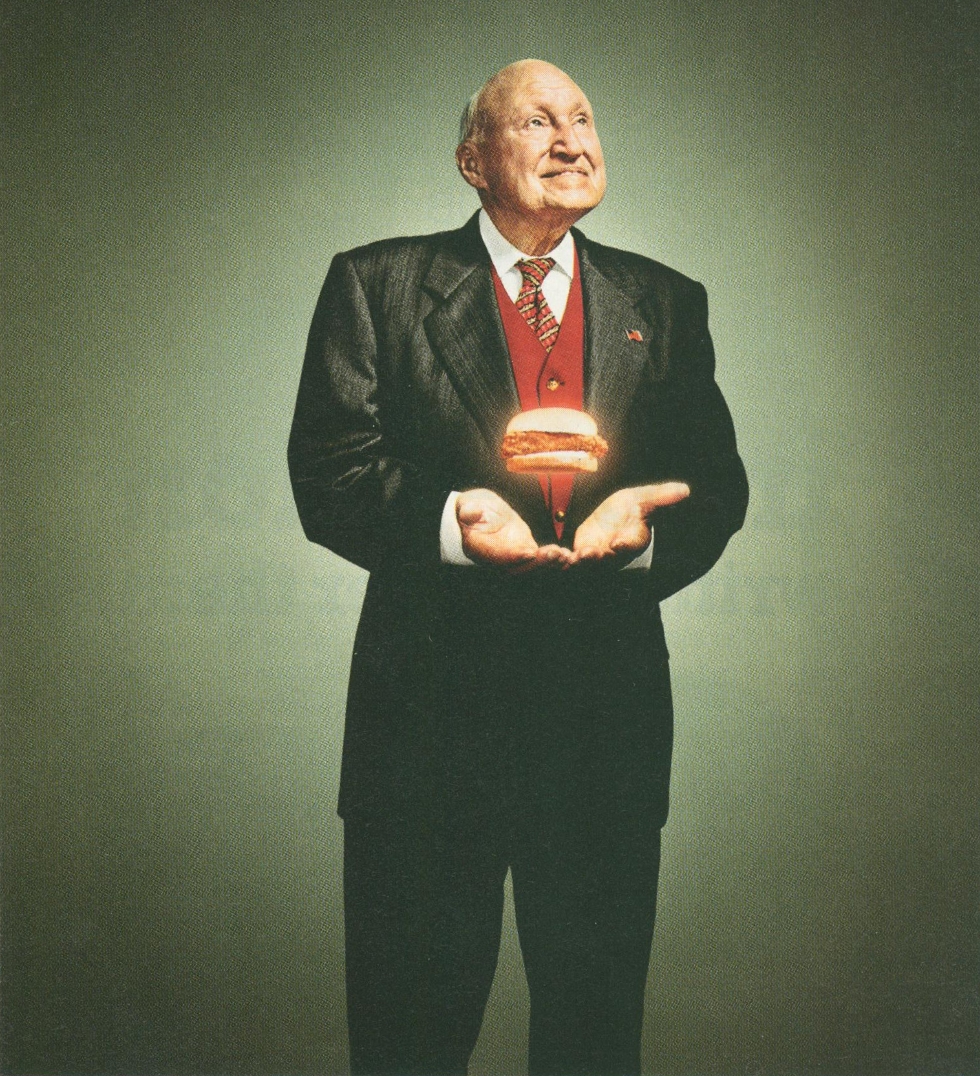

That chicken sandwich—floating, glowing, miraculous—was featured in a 2007 Forbes article on Chick-fil-A, an Atlanta-based restaurant chain that currently has about 1,600 separate locations in 39 states. Founded by S. Truett Cathy (also pictured above) and incorporated in 1964, Chick-fil-A is well-known in the South—and increasingly in other parts of the U.S.—for a menu that includes the standard fast-food fare of soda, milkshakes, and (waffle-cut) French fries as well as southern staples like sweet tea and carrot n’ raisin salad. But it is most well known for its signature chicken sandwich.

In real life, nothing about a Chick-fil-A chicken sandwich makes it illuminate and levitate. Best I can tell, its culinary chemistry is as follows:

– Two buttered hamburger buns

– Two sliced dill pickles

– One boneless, skinless chicken breast, battered and pressure cooked

– Salt, pepper, and other “seasonings”

Nothing spiritual there. Again, best I can tell.

Still, Cathy has imbued his chicken sandwiches with a spiritual aura ever since his company started to grow by leaps and bounds in the 1980s and 1990s. That’s certainly one reason why an illustrator for Forbes saw fit to Photoshop a pietà of poultry for the magazine’s story on Cathy and Chick-fil-A. It matched the story that Cathy told about himself, his company, and his chicken sandwich.

The story goes something like this. Born poor (but not too poor) in rural Georgia, Cathy started up a small diner in a working-class neighborhood of Atlanta shortly after World War II. He then set up another diner, lost it to a fire, and switched up his business model to prioritize the selling of chicken sandwiches over burgers. He then moved his operation into the suburban mall market. Then he moved into the strip-mall market. Then he moved into the just-off-the-interstate-exit market. He is now a billionaire. Through it all, Cathy remained a faithful Baptist and a self-professed “born again” evangelical Christian. Thus, Cathy claimed that the success of his sandwiches came not just from good business decisions or favorable market conditions. God blessed his chicken sandwich because Cathy had been a wise and godly steward of his time and talent.

Out of gratitude for God’s gracious affirmation of Cathy’s efforts and ideas, Cathy decided to return the favor. For that reason and that reason alone (again, so goes the story), Chick-fil-A donates millions of dollars each year to youth programs, foster homes, and college scholarships. It sponsors marriage retreats and youth camps. It encourages “God-focused,” evangelical-style dedications at every franchise opening. And, most notably, it requires every Chick-fil-A franchise to close on Sunday.

That chicken sandwich—a product, in Cathy’s estimation, blessed by God because of Cathy’s own faith in the possibility of that work-derived blessing—made all this happen.

How should we interpret this? How do you write about a company that sees its signature product as a spiritualized “good,” in both senses of that word? How do we navigate such a spirituality in the marketplace?

There are a few options, but no matter how you look at it, Chick-fil-A and its chicken sandwich present some dilemmas.

The first is one of taxonomy. Chick-fil-A spirituality fits awkwardly within available definitions. Cathy and many of Chick-fil-A’s executives and employees are evangelicals. Many are classic institutionalists in that they attend churches regularly or support distinct evangelical denominations. And, of course, they work for an organized, bureaucratic institution—the corporation.

Page 1 of 4 | Next page