chicken sandwich

by Darren Grem

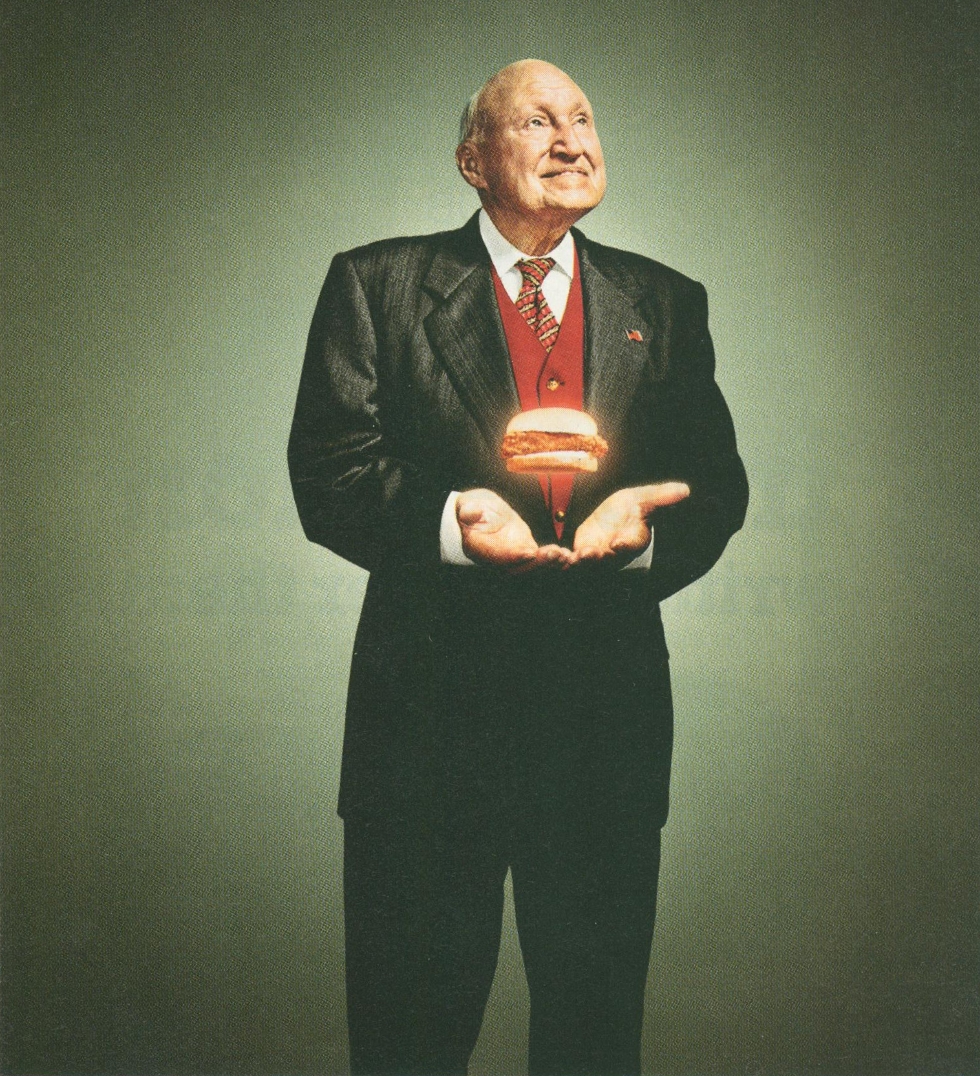

That chicken sandwich—floating, glowing, miraculous—was featured in a 2007 Forbes article on Chick-fil-A, an Atlanta-based restaurant chain that currently has about 1,600 separate locations in 39 states. Founded by S. Truett Cathy (also pictured above) and incorporated in 1964, Chick-fil-A is well-known in the South—and increasingly in other parts of the U.S.—for a menu that includes the standard fast-food fare of soda, milkshakes, and (waffle-cut) French fries as well as southern staples like sweet tea and carrot n’ raisin salad. But it is most well known for its signature chicken sandwich.

In real life, nothing about a Chick-fil-A chicken sandwich makes it illuminate and levitate. Best I can tell, its culinary chemistry is as follows:

– Two buttered hamburger buns

– Two sliced dill pickles

– One boneless, skinless chicken breast, battered and pressure cooked

– Salt, pepper, and other “seasonings”

Nothing spiritual there. Again, best I can tell.

Still, Cathy has imbued his chicken sandwiches with a spiritual aura ever since his company started to grow by leaps and bounds in the 1980s and 1990s. That’s certainly one reason why an illustrator for Forbes saw fit to Photoshop a pietà of poultry for the magazine’s story on Cathy and Chick-fil-A. It matched the story that Cathy told about himself, his company, and his chicken sandwich.

The story goes something like this. Born poor (but not too poor) in rural Georgia, Cathy started up a small diner in a working-class neighborhood of Atlanta shortly after World War II. He then set up another diner, lost it to a fire, and switched up his business model to prioritize the selling of chicken sandwiches over burgers. He then moved his operation into the suburban mall market. Then he moved into the strip-mall market. Then he moved into the just-off-the-interstate-exit market. He is now a billionaire. Through it all, Cathy remained a faithful Baptist and a self-professed “born again” evangelical Christian. Thus, Cathy claimed that the success of his sandwiches came not just from good business decisions or favorable market conditions. God blessed his chicken sandwich because Cathy had been a wise and godly steward of his time and talent.

Out of gratitude for God’s gracious affirmation of Cathy’s efforts and ideas, Cathy decided to return the favor. For that reason and that reason alone (again, so goes the story), Chick-fil-A donates millions of dollars each year to youth programs, foster homes, and college scholarships. It sponsors marriage retreats and youth camps. It encourages “God-focused,” evangelical-style dedications at every franchise opening. And, most notably, it requires every Chick-fil-A franchise to close on Sunday.

That chicken sandwich—a product, in Cathy’s estimation, blessed by God because of Cathy’s own faith in the possibility of that work-derived blessing—made all this happen.

How should we interpret this? How do you write about a company that sees its signature product as a spiritualized “good,” in both senses of that word? How do we navigate such a spirituality in the marketplace?

There are a few options, but no matter how you look at it, Chick-fil-A and its chicken sandwich present some dilemmas.

The first is one of taxonomy. Chick-fil-A spirituality fits awkwardly within available definitions. Cathy and many of Chick-fil-A’s executives and employees are evangelicals. Many are classic institutionalists in that they attend churches regularly or support distinct evangelical denominations. And, of course, they work for an organized, bureaucratic institution—the corporation.

But they also exude a kind of non-sectarian spirituality that is highly individualistic, captured by notions of spiritual transcendence, and strongly informed by the possibility of participatory engagement with the divine or sacred or “authentic.” Moreover, their Jesus and God and Bible are not very specific in terms of moral injunctions or “truth” statements, although Chick-fil-A executives and customers vary on that point. Still, they generally eschew the us-versus-them worldview and turn-or-burn rhetoric of a Jerry Falwell or Pat Robertson. Indeed, most affiliates of Chick-fil-A are quiet—or at least not very public—with such views, even if they hold them privately. As a result, only on rare occasions have they been cast and criticized as exclusivists with their religious or spiritual claims and practices.

More often than not, Chick-fil-A sees “faith” not as ammunition in a cultural war but an inspirational resource for personal uplift and empowerment. If it’s activism, it’s of a different type than the kind of explicit public politics of the Christian Right. It is instead a kind of nice-and-smiley spiritual activism. “Faith” means “having faith in faith” and using the power of positive thinking to self-actualize and attain personal purpose and, by proxy, broader social influence. Maybe all that doesn’t fit cleanly into a definition of spirituality, which can be—let’s admit it—a shifting, amorphous, “know it when you see it” kind of category. But it sure does seem like they are trying to be “spiritual but not religious”—or at least prioritize the “spiritual” over the “religious,” while maintaining a distinct sense of trying to change the world, one chicken sandwich at a time.

Another dilemma in our parsing of Chick-fil-A’s spirituality is the problem of misdirection. If we nod along with what Cathy claims about his sandwich and his company, we risk ignoring or downplaying or overlooking or justifying the processes that actually made the chicken. Skinless, boneless, battered, and butter-bunned chicken filets do not appear ex nihilo. Chicken farmers, sometimes in debt to large-scale processors and often struggling to make ends meet in the contemporary agricultural market, hatch and raise the company-owned chicks to maturity. Workers—often Latino, sometimes undocumented, usually uninsured and underpaid—in poultry plants wash, slice, and cut the live chickens for Chick-fil-A. Truckers drive the chickens to slaughter and then drive ready-to-cook cutlets to every Chick-fil-A distributor or franchise. Hourly part-time employees, often teenagers or college-age young adults, cook the chickens behind the counter at Chick-fil-A and then sell them to customers, who likewise invest whatever meaning or desire they want into the sandwich.

All of these people contributed their time and talent to the chicken sandwich, not just Cathy and certainly not some vague collusion of spiritual entities or forces. Some of these people contributed so much more.

ALBERTVILLE [AL]—The federal government has proposed $59,900 in fines for Wayne Farms LLC after a teenage worker died at its Albertville poultry-processing plant in April, labor officials said Wednesday. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s investigation of the accident found the worker, 17-year old Augustin Juan, was trying to free a stuck door on a bird cage when he was crushed between two cages. “These so-called ‘struck-by’ accidents are a leading cause of worker death in the Southeast,” said Roberto Sanchez, OSHA’s Birmingham-area director. . . . Company representatives could not be reached for comment Wednesday.

– The Gadsden Times, September 23, 2004

Wayne Farms LLC was—and still is—a major supplier of processed bird meat to Chick-Fil-A.

If there’s something spiritual to the sandwich, then it cannot become a glare that blinds us. Indeed, spirituality—something arguably protected by the First Amendment—potentially makes the corporate workplace a sacred site and, therefore, off limits to outsider involvement and critique. If anything can be claimed as spiritual in a work environment, then everything might be permissible, from beneficial social service to human catastrophe. That might sound alarmist. But it stands to reason that we should ask why a company might want to be the arbiter of spirituality and, therefore, a producer of the sacred that should be respected and accepted, more so or at least on par with those entrusted by the public to keep business within the limits of the law, as voted on and written. Indeed, the fact that many corporate CEOs liken notions of “spirituality” and “faith” as the key to “leadership” at work should make us pause and ask: Who made you God? If we understand spirituality in the marketplace as somehow divested from the marketplace and the people and decisions that make it up, then I’d argue we are not really doing our jobs. At best, we are studying hagiography. At worst, we might be enabling the use of “spirituality” by corporations as a kind of regulatory antidote.

What, then, are other options? I think any understanding of material goods made and sold by any company, especially self-declared “spiritual” companies doing “spiritual” business, needs to be grounded in the human element. It just has to be, whether it’s a copy of I Ching or a falafel or a “Jesus is My Boyfriend” T-Shirt or an iPhone 4S or a 3D-HDTV or a $35,000 industrial sprocket or a $35 shovel. That is not saying that we cynically dismiss the spiritual as de facto corporate cover—as merely the smoke and mirrors of the marketing and P.R. department. But we do have to recalibrate. Physical goods and personal services—and the men and women who make and price and value and sell them—are not quite like analyzing the “spiritual” in prophetic ecstasy or tribal song or mural-gazing or a contemplative moment by a lake. Material production and spiritual or quasi-spiritual fetish can and do intersect, just as Marx, Weber, and others have said.

But they also do not do so in simple, direct, and always predictable ways. The spiritual is not just a product of the material. The material is not quite a product of the spiritual. The chicken sandwich, again, stands before us with multiple and complex spiritual meanings which must be dealt with because they are there—stubbornly there—instead of not being there in the face of corporatization. Cathy’s chicken sandwich didn’t need to float and glow. Plenty of products and services are made, sold, and bought without overt spiritual overtones. Why Cathy and his company injects spirituality into the process of making and selling chicken sandwiches stands as a dilemma not quite explained by raising awareness about Chick-fil-A’s supply chain. Moreover, calling the company on the carpet for its lack of awareness or interest in that supply chain seems too easy, especially if we don’t seek to understand how Chick-fil-A’s spiritual affectations might hinder or enhance the company’s ability to be aware of or interested in those who sacrifice for its sandwich.

This circles us back to the question I raised earlier. How do we navigate spirituality in the marketplace? Let’s expand that question further by considering how we might address the movement in contemporary corporate America to bring spirituality into the workplace, a movement that Chick-fil-A certainly fits into. Whether you call it a “God at Work,” “Faith in the Workplace,” or “Spirituality in the Workplace,” there is an impetus toward making work mean “something” more than a means to profit-maximization. Why? To what end? By which means? In what ways? It’s also important to ask who is backing such initiatives and why. If Walmart and Tyson Foods are behind you, what does that mean for how we understand God-faith-spirituality at work?

Call it a movement devoted to delegitimizing regulation or killing unions or ensuring the docility of the employed (maybe it’s that). Or, call it a movement devoted to advancing personal self-satisfaction or revitalizing “business ethics” or “corporate social responsibility” (maybe it’s that too). Regardless, spirituality is there in certain corners of corporate America and it’s making singular and multiple, coherent and incoherent claims—while perhaps precluding other claims—about the value of work and human dignity, about the “essence” of the spiritual self, and about the possibilities of spiritual community through commodity-imagining, commodity-making, and commodity-buying.

We can’t take Chick-fil-A’s claims about its sandwich at face value because we lose something in the process. We lose the connection between spirituality and the people who make up the marketplace and the networks and chains that support contemporary capitalism. But we also can’t just dismiss these claims about the spirituality of work, of goods, of companies, of people—or stop with investigative exposés of how it has or has not filtered down to the bottom or up to the top of the corporate triangle. That doesn’t really dive into the messy endeavor to explain spirituality in the marketplace, either as a complicated and layered phenomenon or as an organized but diverse and divided movement.

I have my own thoughts about what history, as I understand it, has to say about the construction of spirituality in the world of buying and selling, of sweating and sacrificing, of hope and fear, of living and dying. I will share them and strive to sell them in the form of a niche or (fingers crossed) mass-market book. I will sell them as an extension of my scholarly persona in the marketplace of ideas. And, I will probably call my work a “spiritual” enterprise, intended to fill my own wants and needs, to better those around me, or to distract them from my own foibles and failures.

I suppose, then, I cannot saddle up on too much of a high horse when considering the chicken sandwich and those who spiritualize it, especially because I am captured in the same pushes and pulls of motive and morality and materiality in the contemporary market.

I also cannot do this because—despite what I have read and written, despite what I have averred, despite what I wish was and was not there –I must confess.

I have tasted and believed.

The Chick-fil-A chicken sandwich is like heaven on earth for less than five bucks.