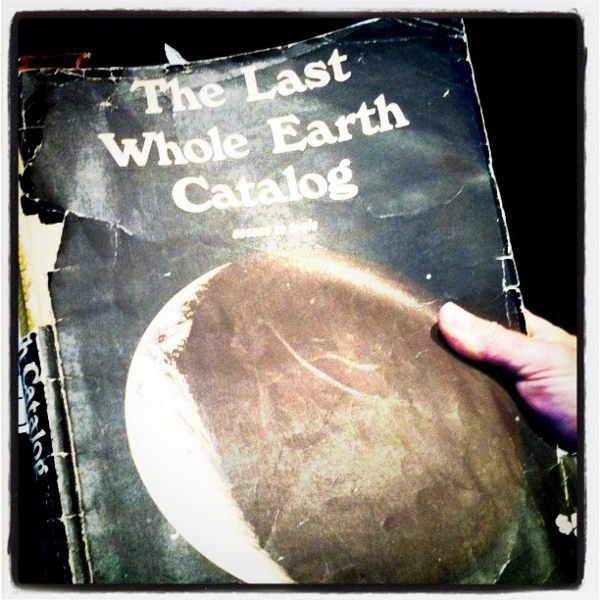

Their titles were always momentous: The Next, The Ultimate, The Last. I was a literalist as a child, and I believed that the Whole Earth Catalogs contained the Whole Earth. They didn’t really seem like catalogs though, in the way the L. L. Bean and Johnny’s Selected Seed catalogs were in my parents’ house in rural Maine. The Catalogs were the tallest black spines on the white-painted bookshelf by the window in the living room, the Reference Shelf. My father would occasionally leap up from dinner and snatch the Oxford English Dictionary (condensed) or the Encyclopedia Britannica from this shelf. He would nudge his gold Lennon glasses further down on his nose, and intone triumphantly the wisdom contained there on the tissue-thin pages. These books contained authoritative answers; though they might occasionally be cross-referenced one to the other, the connections among them didn’t expand past the reference shelf.

But the Whole Earth Catalog was different. Though it resided on the same shelf, the sprawling, messy, self-deprecating celebration of accidental discovery was perhaps less related to the condensed Oxford English Dictionary than it was to the inhabitants of my parents’ other bookshelves: Helen and Scott Nearing’s homesteading chronicles, and M. Scott Peck’s nontraditional parenting guides. As in: they were all blueprints my parents had tried to follow, imperfectly. The Whole Earth Catalog represented the adventure and freedom of San Francisco, flowers-in-the-hair hippie-dom to my father, hardscrabble WASP Protestant by birth whose own spiritual sense was closer to New England transcendentalism, with its abstract, cold-weather visions of solitary fortitude. Having chosen to separate themselves, geographically, from family and friends, in favor of living a principled life in eastern Maine, they still hungered for the sunny, chaotic, Merry Prankster-style life.

The Catalog wasn’t the sort of thing you could flip through to find the answer to a specific question. I tried, and always ended up being infinitely side-tracked into an alternative universe of compost-able sleeping bags, houses built of old milk containers, the latest works of R. Crumb. Each entry seemed to be a prophecy of another world, an item that would only be useful in one single situation far removed from my ordinary life. The Catalog made it possible to imagine such situations, which was both exciting and terrifying. Each page looked different, some enclosed in a black border, handwritten and typeset words wandered among line drawings, diagrams, pentagrams, names and addresses to write away to. That was the thing: the Catalogs didn’t really exist, couldn’t really exist, in isolation. Their pages spoke directly to you, implored you to take action, to connect.

Once in his pot-smoking youth, my father was flipping through a Whole Earth Catalog when he had a semi-mystical experience: the book was calling to him. In a note by Ken Kesey, spiritual brethren of the Catalogs’ creator Stewart Brand, my father thought he saw his name “Henry.” This prompted him to find Kesey’s phone number and give him a call. As he and Kesey pored over the Catalog from their two ends of the country in Maine and Oregon, my father realized sheepishly that the word he’d thought said “Henry,” actually said “learn.” Kesey told my father: “Don’t worry, the same thing happened once with me and William Burroughs.” He left Henry with some parting wisdom, passed down to me as “keep on keeping on.” His message might just as well have been “Only connect.” Though you may feel yourself to be a solitary principled person, you are in fact part of a long, messy lineage of spiritual seekers. And that act of reaching out is never a mistake, because it connects you to a wider world; you don’t have to go it alone.

I always thought the most amazing part of this story was that my father could find Kesey’s number and that Kesey took his call—that was back in the seventies, before the Internet. How did you know where to find anybody? The Catalog, much more so than the Yellow Book, had magical powers of connectivity. Maybe that was why we kept them so long the biodegradable pages started to yellow and the glue in their perfect-binding started to erode. Years later, I learned that Stewart Brand had gotten off Ken Kesey’s bus and become one of the early inventors of the Internet; I can’t say I was surprised. I only hope he endowed it with the same impish spirit of merry mayhem that animated the Whole Earth Catalog.