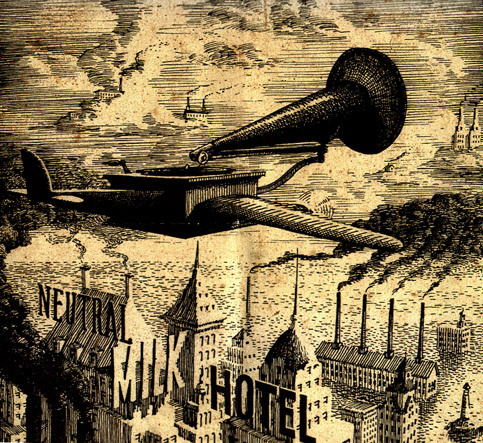

Neutral Milk Hotel, In the Aeroplane Over the Sea

by Joshua Dubler

I’ve been avoiding this assignment for weeks. Somewhere in this mix of postponement is the reverent caution emitted by what the more spiritually confident might call “the sacred,” a power that can render even the most sacrilegious among us a John of Silence. Can zealous speech do anything other than betray the object of its devotion?

Comparatively speaking, 1998 was a rather dead time to be alive. In the three quarters of a century that American youth has lived its life through the soundtrack of popular music and masqueraded in the styles that go with it, never has a subculture had so little affect as indie rock. Neither dramatically decadent nor morbid, indie rockers were, by and large, simply muted and flat, unmovable. There was resistance in this reticence, a savvy After-Adorno suspicion of the saccharine earnestness of stadium rock and the illusory sentiment conjured in stagecraft’s glare. That is to say that like all identities, indie rock was an identity of opposition. And yet, its resentment suffered sorely from the lack of a suitable object. These were white kids, disproportionately. Reagan was gone, the Cold War was over, and the economy was strong. Without anything to get too worked up over, indie rockers adopted the posture of satisfied bemusement, and the conviction, above all else, to not be fooled again. Read in its own terms (which were essentially those of historical materialism) the languid understatement of indie rock makes all sorts of sense. And yet, the oddity must be stressed: here was a musical subculture whose music knew no dance.

Indie rock had its zealots: earnest makers of sound and taste who circulated in back-to-culture networks of artistic production and appreciation. Based in Denver with a satellite on the hallowed ground of Athens, Georgia, the Elephant 6 collective was one such clique. Contrary to the dominant mood, these people were in no way cool. Perhaps none was less so than Neutral Milk Hotel’s romantic genius of a front man, Jeff Mangum. For those who knew him—and only too soon, those who didn’t—Mangum was a tamer of inspiration, a channeler of visions, an oracle.

A tentative sidebar on the spiritual: even and especially for those hungry American souls that can remember a time before when, rifling one day through the attic, they stumbled upon the faded telegraph report bearing the unfortunate news that God was dead, the irruption that Mircea Eliade dubbed hierophany retains an antecedence in experience. In nature, in love, and perhaps most frequently, in the intimate solitude of recorded music, a moment in time has the capacity to explode with exuberance, devastation, or in a wash of meaningfulness without name. And as the silly theory goes, in the wake of such explosions, grooves of significance are cut in the score of time. And so, for periods of days or weeks of even years before repetition goes stale and our attention is pulled in the direction of further novelty, a path through the woods becomes a discipline, pillow talk becomes a catechism, and an album becomes a liturgy to be hollered at the top of our lungs as the interstate flies by.

So it has been for many with the revelation pressed in plastic as Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeroplane Over the Sea. That those first undone by the album were predominantly disaffected ironists calls to mind midrashic meditations over the characterization in Genesis of Noah as a righteous man in his generation. What work, the rabbis ask, does the temporal qualifier—in his generation—perform? Does it accentuate or mitigate the degree of Noah’s righteousness? The same might be asked of Aeroplane. It might well be the case that 1969 saw the release of ten records with such savage spirituality and that my testimony is merely the travelogue of a rationalist blinded by only the dim light of the cave’s mouth. Or, perhaps, the fact that this force of an album emerged from such a wasteland is precisely what makes it a reasonable bet that the children of my children’s children will know it to some degree.

Here, where I strain to describe the album so as to make it available to the uninitiated reader is where things can only go awry. Nevertheless, let me try and fail to share with you something awesome.

In sound, the album is a circus: punk gives way to folk, which dissolves into a sonic mess and congeals back into rock ‘n roll. Slowed down, the title track’s simple GCDG chord progression could well be reinterpreted as doo-wop. At the core of the album’s instrumentation one can surely pinpoint a rock band, but these elements are wholly enmeshed in a melee of organ, banjo, saws, assorted white noise makers, and a Salvation Army Christmas band horn section, all of which warble collectively from frenzy to dirge. Time and again, the arrangement dissipates and we find ourselves with only Mangum’s voice, rough and raw if not unpretty, alone save for a guitar and a four-track recorder.

The album sets its scene in an American landscape replete with broken families, surreptitious couplings and, presumably, the sorts of winged phonographs one finds aloft over an industrial cityscape on the back of the liner notes and as printed on the CD itself. Its tone is part Chitty Chitty Bang Bang surrealism and part Walker Evans photojournalism, at once jubilantly surreal and brutally ethnographic. As is true of our own world, the world where the album takes place is one of intense wonder and horror. Going on a decade ago I tried to graph the incidence of the album’s recurring tropes. A partial list of that effort reads as follows: death, trailer trash, suicide, I-thou love, domestic violence, incest, the miraculous, music, ghosts, sex, nature, destruction, eyes, mouths, Jesus Christ, abandonment, fetuses, birth, third-person love, shared hatred, carnivals, life as seen from the outside, semen and other bodily discharges, nostalgia, myself, flesh, sister, angels, wings, spines, faces, dreams and speakers.

As a fragment in the genealogy of spirituality, special attention is due to the recurring theme of the two-headed boy. Unmasked on the album’s fourth track as an undead laboratory curiosity, the two-headed boy is the exception that proves the existential rule that, as Aristophanes dubiously reports it in the Symposium, we are, each of us, the divided half of a broken human union. It is the myth that has inspired a thousand movies, a million pop songs and, at one time or another, everyone I know. Aeroplane’s version of this myth goes like this: before we are born, when we are in utero with our unborn twins, we are whole. After we are dead, when we meet on a cloud and laugh out loud with everyone we see, we are together again. In between, for the duration that we are thrown into the world, we fumble toward one another like adolescent lovers who have not yet mastered their body parts. Not always, however, is our differentiation unbridgeable. By making beautiful things—love, children, music—we may find fullness even as we live, united with one another and with God.

Yes, believe it or not: God. Bursting forth from an atmosphere of unformed reverb between the album’s first and second tracks, Mangum’s plaintive voice offers the most unanticipated praise:

I love you Jesus Christ

Jesus Christ I love you,

Yes I do

The voice repeats what it recognizes to be a truly shocking declaration. Whatever can this mean? In the unbroken block of prose of the liner notes, where the lyrics at times yield to second order reflection, an explanation is proffered.

…and now a song for jesus christ and since this seems to confuse people I’d like to simply say that I mean what I sing although the theme of endless endless on this album is not based on any religion but more on the belief that all things seem to contain a white light within them that I see as eternal…

A disavowal in no sense, to an audience that can only assume he must be joking, Mangum makes clear that as crazy at it may sound, he means what he says. And yet, as he translates for the godless, his love is meant without a shred of exclusivity. Not based in any one religion, Jesus Christ here is a metonymy for the endless endless, the seemingly eternal white light that animates all things. Mangum’s God is one that even a secularist can abide, just so long as she knows what it’s like to be a body in a state of unwilled differentiation. In the album’s penultimate stanza, where the two-headed boy bids sad farewell to his soon to be broken-off half, just as Mangum, himself, prepares to say goodbye to the beloved that he will soon bequeath to us, the listeners, this God is further fleshed out:

And when we break we’ll wait for our miracle

God is a place where some holy spectacle lies

And when we break we’ll wait for our miracle

God is a place you will wait for the rest of your life

In my early years with the album, when I was still very much under Nietzsche’s spell, I made poor sense of Mangum’s faith by shoehorning into the first pair of these lines the intimation of the dissimulative character of the divine presence. God as a place where some holy spectacle lies: this would be something along the lines of God and not-God in an extra-theological sense. More recently, however, as my will to demystify has courted its other half, it has been the latter lyric in which I have found disclosed the fullness of the album’s theology, which is also to say, its anthropology. For in the play between “God is the place you will wait for / the rest of your life” and “God is the place you will wait / for the rest of your life,” we find a God at once transcendent and immanent, both achingly wanting and radically present. It is a God that presides over and resides in a world saturated in the beauty and horror of the sublime, which, even at its cruelest, always merits wonder. As the title track concludes in a declaration that comes as close as the album gets to prescription: “can’t believe how strange it is to be anything at all.”

Ignoring for a moment this gentle model of righteous giddiness, I will conclude on a petty note, though one again germane to the genealogy at hand. For these very texts—the potently spiritual ones that inspire in us the impulse to proselytize—breed covetousness, a resentment in this case directed toward those over-readers who would restrict the bounteous spirit of this doctrine-less Word. From my jealous perspective, the emergent standard read of this cult album is just such a travesty. “An Anne Frank concept album,” is how one undergraduate characterized it for me to my dismay. “But,” I wanted to say, “Don’t you see? The album is about…everything!” Which I truly take it to be.

Fault for the Anne Frank reduction may be pinned on Mangum himself, who in an interview with a fleetingly influential magazine at the time of the album’s release identified the famous martyr as his muse and conversation partner. Shortly thereafter, the band broke up and Mangum vanished from the public view, not yet to reemerge. Because the prophet was now in occlusion, the interview—along with similar comments made by Mangum at the time—became the key for unlocking the album. This is to say that these texts became the key for defacing it. Beyond irresistible allusion, I won’t regale you with accounts of rock operas inspired by the album featuring high school children dressed as concentration camp inmates. The internet could provide that, if you like. Suffice it to say, the attempted sacrifice of Aeroplane to the Holocaust affirms a longstanding irritation of mine with the sundry transcendental signifiers of the secular, which dwell in its inner sanctum: the spiritual. As poisonous and stupid as God may have been for discourse—and He can well be—not by killing Him alone do we forego the analytic capabilities to violate the glories of creation.