telegraph

by Jeremy Stolow

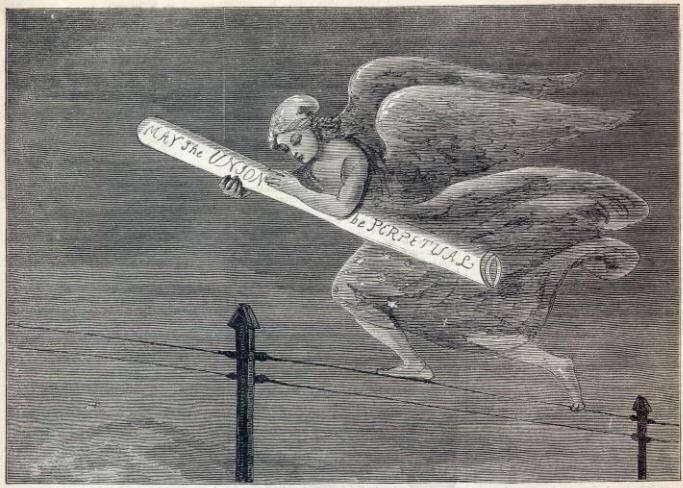

Nestled on the back page of a November 1861 edition Harper’s Weekly appeared an image celebrating the October 24, 1861 inauguration of the first transcontinental telegraph line. Although the illustration was published with no accompanying article, given the context of the rest of the magazine—devoted almost exclusively to reportage of the progress of the Civil War that had broken out in the USA earlier that year—it would be hard not to hear a political resonance in the words, “perpetual union.” Indeed, the very first telegram transmitted on the new line testified directly to this resonance. Addressed to President Lincoln in Washington, D.C., the telegram spoke of Californians’ “loyalty to the Union and their determination to stand by the government on this, its day of trial.” This was a pledge of allegiance, not only in response to what had already become a devastating war of partition, but also in support of a grand project of technological modernization: the engineering of a new physical and social world in which the most remote hinterlands would be linked directly to the deepest heartlands of government, industry, and culture. Even more profoundly than the postal system and print industries that preceded it, the electromagnetic telegraph invoked a coming age of free exchange and virtual tele-presence. This new vision of wired nations and unchained spirits is dramatically depicted by the image of an angel, moving as lithely as a tight-rope walker along the telegraph wire, her wings folded in wait for an even more effortless journey to come.

By the time its cables had reached the Pacific Coast, the telegraph had already come to occupy a prime place in the American imaginary, providing (among many other things) a metonym for what Catherine Albanese has called the “kinetic revolution” that was placing new priorities on motion, transformation, and progress in all facets of civil, cultural, economic and political life in the Jacksonian era. Alongside the extension of roads, bridges and tunnels across even the most mountainous terrains, the expansion of the railway system, and increasing opportunities for travel by steam-powered watercraft, the telegraph engendered a new, vertiginous experience of “life in the fast lane” and the collapsing of distant horizons through the universal and invisible, but very tangible medium of electricity. Long before Google, Second Life, or the Web 2.0, telegraphy was implicated in the creation of phantasmatic, electrically-mediated communities of knowledge-seekers, conversation partners, and like-minded souls dispersed across the entire globe.

The very first message to reach California on that inaugural day of the new transcontinental line came from Brigham Young, the Mormon leader, governor of Utah, and patron of Western settlement, who rejoiced in the telegraphic strengthening of “the bonds of friendship between the people of Utah and the people of California,” but who ended his salutation with an injunction that pointed to the work to come: “Join your wires with the Russian Empire, and we will converse with Europe.” The Pacific Coast was already no longer visualized as the end of the line. At the very moment of completion of the American transcontinental line, the telegraph’s horizon was extended further, pointing toward an imminent, truly global, frontier-less, and harmonized future.

The choice to depict the bearer of telegraphy’s utopian gifts in the form of an angel was not unique to Harper’s magazine, nor is it particularly surprising. As John Durham Peters reminds us, the figure of the angel has been linked at least since St. Augustine to the idea of instantaneous travel, and angelic speech has been described as a transference of pure, interior thoughts from one party to another without any degradation or loss. “Angels,” Peters summarizes, “a term that comes from the Greek, angelos, messenger, are unhindered by distance, are exempt from the supposed limitations of embodiment, and effortlessly couple the psychical and the physical, the signified and the signifier, the divine and the human. They are pure bodies of meaning.”

But as it so happens, angels were not the only spirit entities who presided over the completion of the telegraph line, and not all these transcendent powers worked toward the same end. In his memoir published in The Californian magazine in 1881, James Gamble—the pioneering figure responsible for laying the cable that connected San Francisco to Salt Lake City, as well as much of the rest of the telegraphic infrastructure along the Pacific coast—recounts the many challenges he faced setting up the line. His narrative details the extended effort to manage hostile terrains, difficult weather, pack animals, a less-than-reliable workforce, and, not least, the delicate negotiations needed to win the assent of local Indian populations, specifically the Shoshone people, whose territories at that time extended from Western Utah across Nevada and into Eastern California, precisely along the route of the Overland Pass, which had been chosen for the construction of the transcontinental line. A striking feature of Gamble’s story is the recurring manifestation of magical and spirit forces, control over which seemed decisive for the success of Gamble’s enterprise. At times, Gamble’s journey resembles that of an itinerant magician, an electrical showman trading in mysterious demonstrations designed to both educate and awe his audiences. One such spectacle was performed during the opening of the first telegraph office in San José, California, where a crowd of curious onlookers had gathered to bear witness to new technology at work. Gamble writes:

Observing the anxious and inquiring expression on the faces of those who had managed to get near enough to thrust their heads through the open window, it occurred to me to act in a very mysterious manner in order to see what effect it would have upon my spectators. … [As] I was preparing the message for transmission … instead of handing it to the boy for delivery, I put it, holding it in my hand, under the table, which was provided with sides sufficiently deep to hide the envelope from their view. As I did this I kept my eyes fixed on the wire, while, with my right hand, I took hold of the key and began working it. The moment the crowd heard the first click of the instrument they all rushed from under the veranda out into the street to see the message in the envelope pass along the wire. On seeing them rush out tumbling one over the other to catch a glimpse of the message, we on the inside burst out into one long and continued roar of laughter. … The telegraph was to them the very hardest kind of a conundrum. It was impossible of solution. Their final conclusion was that it was an enchained spirit—but whether a good one or an evil one they could not quite determine—over which I had such control that it was obliged to do my bidding. Under this impression they departed one by one, looking upon both the telegraph and myself as something, as the Scotchman would say, ‘uncanny’.

This “very mysterious manner” of acting and its “uncanny” effects belong to a long history of technological wonder-making in the service of public edification, profit, and boundary-maintenance with respect to scientific literati and their abject others. In this case, Gamble’s mastery of the art of legerdemain provided fellow telegraph operators with the opportunity to revel in the naïveté of their technologically illiterate onlookers. But working wonders also proved useful to the company’s efforts to pacify potentially hostile populations and thereby to secure control over territories marked out for extension of the telegraphic infrastructure. A telling instance was Gamble’s way of dealing with Sho-kup, chief of the Western Shoshone tribe that lived in the Ruby Valley in northeastern Nevada, which lay directly along the Overland Pass. In order to win Sho-kup’s assent to the construction of the telegraph line, Gamble had one of his agents lead him on a tour of a working telegraph station, whereupon Sho-kup

was told that when the telegraph was completed he could talk to [his distantly located wife] as well from there as if by her side; but this was more than his comprehension could seize. Talk to her when nearly three hundred miles away! No; that was not possible. He shook his head, saying he would rather talk to her in the old way. His idea of the telegraph was that it was an animal, and he wished to know on what it fed. They told him it ate lightning; but, as he had never seen any one make a supper of lightning, he was not disposed to believe that.

For Gamble and his men, it seems, the telegraph was a magical tool for transcending not only distance but also the privations of “the primitive mind.” Sho-kup, however, was hardly the primitive that Gamble makes him out to be. While it seems that Sho-kup was indeed mystified by the telegraph’s secret modus operandi, his reaction was not based on a total lack of familiarity with the media technologies that were ushering in a new modernity in the mid-nineteenth century. For, as we learn later on in Gamble’s memoir, Sho-kup was already an eager participant in the emerging economy of photographic portraiture, availing himself of the powers of self-representation that were being dramatically reworked thanks to the spreading technology of the photographic camera. Gamble recalls how, at the closing of his encounter with Sho-kup, he:

presented me with a daguerreotype of himself in full dress, taken in Salt Lake several years before, begging me to receive it as a mark of his appreciation of the kindness I had manifested toward him. This was accompanied by the request that on my return home I would send him a portrait of myself. I promised to do so, and on arriving in San Francisco had myself photographed … [and then] placed [the picture] in a gold double locket, with a chain, so that it could be worn around the neck, and forwarded it to him through the Indian Agent, who afterward presented it to Sho-kup with great ceremony.

In this exchange, which of the actors is “the primitive” and which is “the modern?” Perhaps an answer can be found by taking stock of the remarkable collection of material, technological, and phantasmatic entities populating Gamble’s narrative: telegraph operating instruments; invisible flows of electricity; sleights of hand; superstitious minds; enchained spirits; monstrous, metallic animals that live on a diet of lightning; and photographs destined to serve as talismans, yoking their wearers into bonds of distant friendship and strategic alliances. It is hardly insignificant that most of these magical forces were mobilized not by Gamble’s putatively gullible audiences or by the primitives he encountered along his journey, but by Gamble himself. By projecting the presence of spirits, assigning magical explanations, and offering supernatural gifts, Gamble had joined the ranks of what was emerging–not only in the USA—as an advancing army of proselyte-engineers, whose mission was to expand and secure general acceptance for the telegraph through the promulgation of magic. Like the Biblical Aaron beating the Pharaoh’s magicians at their own game, the protagonists of telegraphic modernity forged consensus for their project through the creation of “better,” “more impressive” magic.

By the time of Gamble’s epic journey, an appreciation of telegraphy’s transcendent, magical nature had already been well established in American popular culture. Not least in the case of Spiritualism, a movement whose development precisely overlapped with the rise of the telegraph. One particularly prescient observer of the telegraph’s apparent promise to render distance obsolete was the Universalist minister and trance speaker, John Murray Spear (1804-1887). In 1854, Spear was the recipient of detailed plans, provided to him in a trance state by the spirit of Benjamin Franklin, for the construction of a “soul-blending telegraph.” The soul-bending telegraph was an intercontinental telepathic transmission system to be powered by a corps of sensitized mediums installed in male/female pairs in high towers. This network of harmonized spirit mediums promised stiff competition with existing telegraph services, which were still beset by operational difficulties, and which had yet to announce success in the ongoing effort to connect distant continents. Spear thus imagined an imminent future of communicative harmony on a global scale, a utopian dream to which the crude workings of the electromagnetic telegraph only imperfectly pointed. As it turns out, Spear’s plan was never implemented. But its mere example provided Spear with a vantage point from which to denounce the undemocratic character of telegraphic globalization as it was actually coming to fruition in his day. Commenting on the (at the time, yet-to-be realized) project of the American industrialist, Cyrus Field, to lay a submarine telegraph cable across the Atlantic Ocean, Spear writes:

The purpose is a laudable one, and should be encouraged; but it is seen that such a means of communication would be exceedingly expensive, and, of necessity, would rarely accommodate the poorer classes, while it would enrich others. It is a hazardous scheme—the most so of any proposed. In that submarine wire lies the snake of a most dangerous monopoly.

Who living in our contemporary moment, marked on the one hand by fantasies of hyper-connectivity and techno-transcendence, and on the other by the specter of sinister corporate intentions and digital divides, cannot hear the echo of Spear’s cry?