spirituality, german

by Ludger Viefhues-Bailey

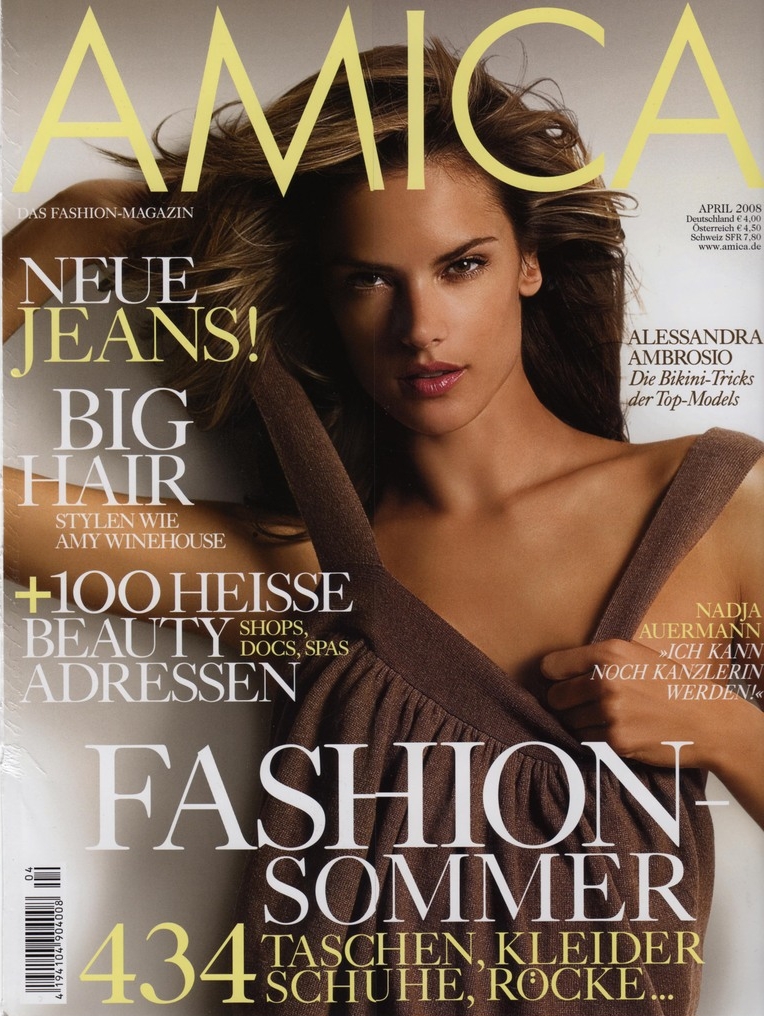

The most important item on my agenda when traveling home to “the old country” is scheduling some time with a German stylist. Not only do these visits keep me up-to-date in terms of hairstyles but they allow me to immerse myself in a wealth of “lifestyle,” “fashion,” and “wellness” magazines. Amica, Die Bunte, and Meine Freundin, to name just a few, provide a wealth of information for how their primarily-female audience can lead fuller lives. As a scholar of religion, I was thus tickled when, beginning in the 2000s, a new feature appeared alongside the usual advice on dieting, exercise, work-life-balance, and sex: spirituality.

Amica, for example, states that spirituality is not a word that refers to the allegedly dubious practices of card reading or palmistry but one that expresses a “feeling of faith beyond all religions.” This source of energy “between mind and matter” points to a dimension of our lives that, if we cultivate it, can lead to more contentment and freedom. Thus, in Amica, I can find not only the “Sex-Check” to discern whether I am more prone to wild or romantic erotic encounters but also the “Enlightenment-Check.” This test allows me to measure how far I have advanced on the path to developing my “true spiritual being.”

When I first encountered spirituality in these magazines, I suspected that its arrival in German stylist salons finally proved Max Weber right. After all, the intense individualization of “spirituality” could be understood as a prime example for the privatization and commoditization of religion in modernity. In secular societies, one could say, religion becomes so profoundly privatized and disconnected from its traditional contexts that its remnants appear open for individual and market manipulation in the form of “spirituality,” a point Jeremy Carrette and Richard King explored in their Selling Spirituality: the Silent Takeover of Religion. A prime location for the new commodity “spirituality” is the market of self-improvement products, as witnessed not only by my lifestyle magazines but also by the flurry of offerings for the “spirituality for managers,” breathing techniques for teachers, and the like. I will become a better me through developing my spiritual self. And Amica helps me to see how far I’ve come and how far I still have to go. As the new dimension of human flourishing, the spiritual makeover is promised and facilitated by a market product, namely the magazine and the places for its consumption, like my stylist’s salon. As I am waiting for my body’s transformation I can muse on the improvement of my spirit as well.

But becoming a better self is not to be understood as a private Emersonian imperative. And the workings of religion in modern societies and states are more complex than a simple privatization paradigm would make it seem. Precisely as a market commodity in the service of self-transformation, the discourse of spirituality subtly relates to ideals of citizenship, particularly in the context of makeover culture. How and where we do our shopping—or invest in transforming our homes, bodies, and spirits—determines our access to social capital. As Brenda R. Weber’s Makeover TV: Selfhood, Citizenship, and Celebrity showed, the ideas of self-improvement and self-transcendence are an integral part of North Atlantic cultural enfranchisement.

But let me return to my magazines. Meine Freundin Wellfit ran an article in 2009 about four women who successfully transformed their lives. The piece begins: “Finding spirituality. Loving your body again. Being free, finally.” The first portrait describes a woman who, after outwardly fulfilling work in international politics, moves to a “Tibetan-Buddhist” monastery to live and study. She founds a charity in support of “little monks,” teaches English, and helps out at the hospital. “I am happy every day to have found the life that fits me,” she says, summarizing her transformation. The second portrait presents to us a nurse who lost weight with the help of Weight Watchers, Pilates, and a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostella, while the third is of a former successful lawyer who finds love with a goat-herder in an Alpine village. The last portrait tells the story of a woman who, as the child of “Turkish guest-workers,” had to break radically with her controlling parents to be freely herself and find romantic love where she wishes.

In German folk-ethnology as Chantal Munch and her colleagues Marion Gemende and Steffi Weber-Unger Rotino demonstrated in Eva ist emanzipiert, Mehmet ist ein Macho, the non-German Turkish other is profoundly linked with a sexually-restrictive Islam. It seems clear that the image of a controlling Turkish family evokes a vision of negative religion. In fact, since the 1970s, it has been a trope in German discourse about immigration to contrast the “emancipated” German against patriarchal migrant sexuality. Thus, it would be highly unlikely to find in magazines like Meine Freundin a testimony of a teacher who, based on her “spirituality,” for example, began piously wearing a veil in her classroom. Instead, in subtly playing on the trope of allegedly “traditional Islamic migrant sexuality” this portrait re-inscribes the boundary between German and migrant culture. Moving from the later to former requires a radical break with traditional (read: Islamic) origins.

For the article in Meine Freudin, spirituality is not only a central ingredient of the politics of the makeover. Rather, it also plays a subtle role in differentiating socially acceptable religion that enhances a positive transformation (Tibetan Buddhism) from unacceptable religion (the Islam of the “Turkish-guest workers”). In both functions, “spirituality” contributes to sending clear signals about what we need to do in order to be transformed into good Germans. In other words, attention to “spirituality” teaches us that the privatization of religion is only one move in its intricate dance with the modern state and society. Privatized religion’s contribution to the policing of citizenship via market forces is the other.

Waiting my turn at the stylist and reading about spiritual transformation and emancipation in Amica and Meine Freundin, I wonder: How will a woman who works in or frequents this salon, and who is also a daughter of Turkish immigrants, receive this story of emancipated sexuality? What will the other middle-class customers make of it? It seems clear to me that we who linger at the salon learn not only about the latest fashion but also take home an important lesson about what it takes to “integrate” oneself into what German newspapers call the “majority society.” Spirituality will make you free and help you become, at last, a “true” German.