When travel writer William Least Heat Moon decided to drive the nation’s “backroads” highways that meandered through small towns and “real” America detailed in his classic Blue Highways, he thought that “Maybe the road could provide a therapy through observation of the ordinary and obvious, a means whereby the outer eye opens an inner one.” Maybe it could. At the very least, it might set things in motion and materialize the spirit of American dreams. More than simply a means of convenient transportation, the highway has held out this promise as a significant spiritual technology throughout its American history.

Oh God said to Abraham, “Kill me a son”

Abe says, “Man, you must be puttin’ me on”

God say, “No.” Abe say, “What?”

God say, “You can do what you want Abe, but

The next time you see me comin’ you better run”

Well Abe says, “Where do you want this killin’ done?”

God says, “Out on Highway 61”

— Bob Dylan, “Highway 61 Revisited” (1965)

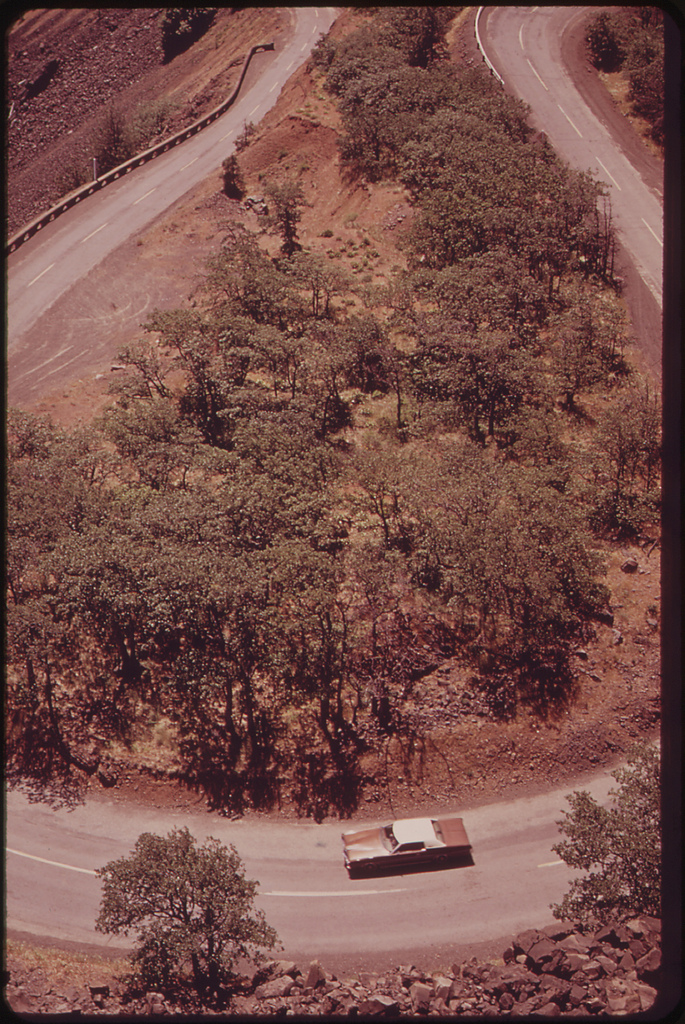

Highway 61. U.S. Highway System (1924). The Interstate Highway System (1956). Route 66. Highway 1. The 101. 95. The names and the routes, the movement through changing landscapes as the roads wind through the mountains and prairies, call to mind other movements and peoples who found hope and purpose, who sought adventure or rebirth on the highway. For me, those connections are visceral: the highway conjures Jack Kerouac’s Beats and Ken Kesey’s Pranksters, who in turn recited Woody Guthrie’s Okies and Utah Phillips’s Wobblies and hobos. Here is a history of an other America that nevertheless has been a defining American experience. These (and many more) mythic figures of American history took to the roads and rails in pursuit of American dreams of freedom and autonomy—ambivalently defined in material, social, psychological, political, or transcendent terms. The common thread was movement across the landscape, typically at one’s own pace and whims. And that movement produced encounters with self and with others in ways that spun out of the everyday into the extraordinary. Kerouac’s novels, for instance, documented continuous religious and spiritual learning from the strangers he met on the road. Kesey’s boundless utopianism and the Pranksters’ experiments with reinventing reality were fueled not just by LSD, but by the mobility of their psychedelic bus traveling the American highways.

But as with most mythic histories, the road’s realities have been far more complicated than the romanticized images conveyed by literature, film, and folklore. The highway’s movement is dynamic and polysemous, transformative in specific relation to the motivations and imaginations of those who travel it. For some, therefore, it is a space of leisure and adventure, a remove from the tediums and conformities of everyday life in the social/consumer/workplace rat-race. For others, it is a space of labor, whether driving a truck or itinerantly looking for a next paycheck, a way to get ahead or at least to keep afloat. For some it is an escape from a life best left behind, perhaps a chance for a practical rebirth, a new beginning in a new place. For others, it may be an extension of a life, or a temporary voyage of discovery with the promise of a safe and comforting return. In any case, the road journey is a passage through time and space that produces potent potential encounters with newness that might challenge the status quo and the everyday. The highway holds potential.

Page 3 of 4 | Previous page | Next page