hyperanimism

by Manuel Vásquez

Brazilians are fond of saying that god is Brazilian. No other country in the world is blessed with so many natural wonders, gifted practitioners of the jogo bonito (the beautiful game–soccer), and a pervasive joie de vivre. This expression, however, has always been uttered with a heavy dose of irony, coupled with the affirmation that Brazil is the “country of the future and always will be.” In the face of recurring repressive, corrupt regimes, and persistent poverty, this future never seemed to arrive. Brazil always seemed to fail to live up to its potential.

Lately, things have changed. Brazil is now a stable democracy with an expanding urban middle class and one of the most dynamic economies in the world. With a blistering 7.5% growth rate, the country seems poised to surpass Britain and France to become the fifth largest economy of the world, and, in the process, to transition from a regional to a global power.

A central dimension of Brazil’s global projection is its vibrant and variegated religious field, which has become a key node in a new global cartography of religious production, circulation, and consumption. From “Neo-Pentecostal” churches that unabashedly espouse a prosperity gospel and resurgent African-based religions such as Candomblé and Umbanda to shamanistic religious movements that use psychoactive substances to induce altered states of consciousness, such as Santo Daime and União Vegetal, and spiritist mediums who conduct bloodless surgeries like John of God, Brazil is now at the cutting edge of a global “hyperanimism,” a transnational outpouring of the Spirit and/or spirits that is redefining the place of religion in late modernity.

This polymorphous global hyperanimism transgresses the colonial gaze that gave rise to the concept of animism in the first place. E. B. Tylor coined the term to characterize what he understood to be the most “primitive” form of religion, namely, the simple belief in spirits. Tylor argued that modern religions such as Christianity evolved from animism as societies and cultures became more complex. Present-day animism, however, is not some atavistic remnants of humanity’s past. Rather, this “New Animism,” as Graham Harvey calls it, is populated by a variety of vital and effective agentic forces that dwell not only in “nature” but in the commodities and images that we consume daily. Present-day animisms thrive by in-forming and using the advanced tools (such as global culture industries and electronic mass media) of a modernity that was supposed to have superseded religion through a relentless process of secularization and disenchantment.

Ever since the days of Aimee Sample McPherson, Pentecostalism has shown that it is particularly adept at bridging the local and global, the personal and universal, by blending popular culture, entertainment, glamor, the latest advances in media, and good old-fashioned face-to-face evangelization to perform the works of a deterritorialized and deterritorializing Holy Spirit. In competition with Nigerians, Ghanaians and, of course, Americans, Brazilians have elevated the performative dimensions of Pentecostalism several notches, contributing to the creation of a global pneumatic culture of the spectacle, a “charismatic corpothetics,” to draw from anthropologist Simon Coleman, that is disseminated globally through the Internet, TV, and DVDs and other religious paraphernalia.

The exploits of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God are relatively well known in this regard. Considered one of the largest Brazilian transnational corporations, the UCKG has 4,700 temples in more than 170 nations, including Angola, Mozambique, the U.K., France, Germany, the US, Japan, India, Australia and throughout Latin America. Every Tuesday night, a dramatic struggle takes place inside UCKG temples. In what church members call sessões de descarrego (sessions of discharge or release), pastors enjoin those suffering from illnesses, domestic conflict, drug addiction, and unemployment to come to the front of the temple. Once there, the possessing spirits that are causing these problems are summoned in the name of Jesus Christ. The spirits, often the Orixás or African ancestors, oblige and come out to insult the pastor and the congregation in loud and distorted voices, twisting and shaking the bodies of their victims. After some verbal sparring through which the head pastor forces the evil spirits to identify themselves and state the tangible injury they are inflicting and why, a hand-to-hand combat ensues. The pastor literally wrestles the embodied demons down to the ground, while the whole congregation screams: “Burn! (Queima!)” “Burn!” “Leave! (Sai!)” “Leave!” Even though this is a very local spectacle, a fight against territorial spirits that afflict specific people, it is also a cosmic struggle waged by a universal Holy Spirit. And it is a struggle that is being filmed and can be seen on YouTube.

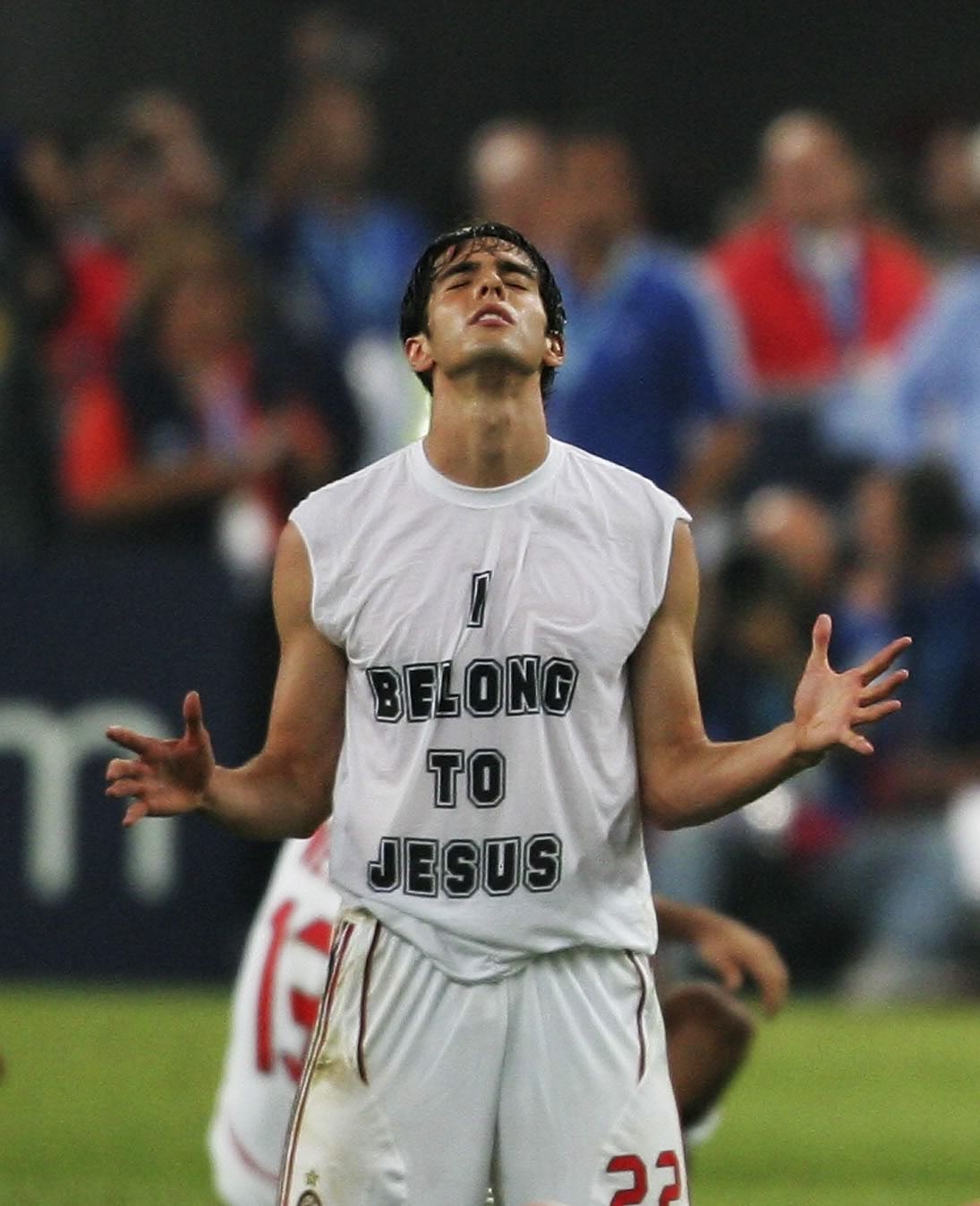

While the UCKG is a global force to be reckoned with, it may no longer be at the forefront of pneumatic innovation in Brazil. The Igreja Renascer em Cristo (Rebirth in Christ Church), founded by bishops Estevam and Sônia Hernandes in the mid-1980s, was described by The New York Times as a vast “religious and business structure that includes more than 1,000 churches, a television and radio network, a recording company, real estate in Brazil and the United States, a horse-breeding ranch and a trademark on the word ‘gospel’ in Brazil.” Renascer em Cristo has also the distinction of counting until recently Brazilian soccer superstar Kaká among its members. By drawing on Kaká’s worldwide visibility, Rebirth in Christ introduces a definite Brazilian flavor to Neo-Pentecostalism’s seamless mixture of business, media, popular culture, and religious performance. Kaká is part of a new breed of Brazilian religious performer-entrepreneurs, who, taking advantage of the country’s world-class prowess in soccer, travel abroad to places as diverse as Japan and Dubai not only to showcase the sport but to spread Brazilian transnational Pentecostalism. These athletes-entrepreneurs-missionaries are performers in a global stage, in a multi-media spectacle. As they score goals, they remove of their team jerseys to reveal “Jesus Saves” or “I belong to Jesus” T-shirts, or torsos tattooed with crosses. They use their bodies as billboards to deliver a holy message for millions of TV viewers. Underlining the blurring of sacred and profane genres, Kaká has declared that he plans to become a pastor after he retires from soccer.

Rebirth in Christ seeks to target the untapped market of a restless young generation who has grown up with a steady diet of images. This is a generation whose lives are deeply imbued with hyperanimism, with a highly mediatized immediacy that blurs the boundaries between virtuality and reality, producing vivid enchanted simulacra, intense self-referential experiences such as being in the middle of combat (World of Warcraft), or being part of a violent heist (Grand Theft Auto) or a plot to kill an important historical figure (Assassin’s Creed). To compete with and co-opt the hyperanimism of contemporary consumerism, youth culture, and cyberspace, Rebirth in Christ has produced its own extreme experiences. After all, as George Bataille tells us, religion is about excess and violent intimacy. Simulating the simulation and re-orienting virtual violence within the framework of pneumatic Christianity, Renacer organizes “extreme fight nights,” setting up rings at churches where pastors and wrestlers clash, showing their technique in vale tudo (literally “anything goes”), a Brazilian type of martial art that mixes multiple styles. These extreme fight nights become “deep plays,” to use Clifford Geertz’s term, where the cosmic struggle between Jesus Christ and the devil is displayed in and through the bodies of the fighters. As in the Balinese cockfight, for followers of Renacer em Cristo attending and participating in extreme nights serves as “a kind of sentimental education,” where a generation weaned on caffeine, adrenaline, and virtuality learns what Neo-Pentecostalism’s embodied “ethos and . . . private sensibility look like when spelled out externally in a collective context.” As a pastor told participants, “You need to practice the sport of spirituality more . . . [y]ou need to fight for your life, for your dreams and ideals.”

Reborn in Christ is hardly alone in creatively reworking the ludic aspects of Brazilian culture and religion. Igreja Bola de Neve (Snowball Church), founded by beach-goers and surfers, has specifically targeted Millennials and the Net Generation through a hip mixing of Christian reggae, rock, and Brazilian funk with avid blogging, surfing, and other extreme sports. Bola de Neve now has churches in places as diverse as India, Canada, Russia, the U.S. (Los Angeles) and Australia, where it has a célula (cell) in Harbord, close to the Sydney’s northern beaches. Other churches include video games, tattoo parlors, and child miracle healers as part of their outreach strategies.

All these examples point to a pervasive hyperanimism, a thorough spiritualization of the material and materialization of the spiritual that characterizes late modernity’s dialectics of over-production and scarcity, virtuality and reality, mediatization and immediacy, and of visibility and invisibility. Pneumatic religions are truly at home amid these dialectical spirals, produced and disseminated by new national and transnational actors and media in an emerging post-colonial economy of the sacred. Scholars need to develop a new transnational, comparative-yet-non-totalizing, post-Hegelian phenomenology of the spirit capable of taking into account the creative and diverse embodied and emplaced interactions among pneumatic religions, capitalism, media, sports, entertainment, and popular culture, interactions which are taking place at multiple nodes in a polycentric global cartography of religious production, circulation, and consumption.