The “camp” where the Star Wars aura began for me in the summer of ’77 was really a two-week babysitter as our parents attended talks and sessions as part of “staff training.” This was the annual gathering of Campus Crusade for Christ staff members from around the world. In other words, my primal cinematic experience occurred in the midst of a bastion of a budding brand of evangelicalism, just then filtering across the country. Many of these evangelicals had been to the conservative-Christianity-meets-pop-culture event called Explo ’72. Many of them were interested in the “born-again” Democrat Jimmy Carter, then in office, but had yet to fall under the spell of thespian-evangelical trickster, Ronald Reagan.

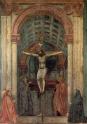

Nobody seemed to care much about the potential theo-politics of Star Wars. Only a few seemed to identify usable theology in it. Some deployed the film to repeat Christian-sounding messages (The Force is God), or to capitalize on the mythic parallels between Obi-Wan and John the Baptist, Luke Skywalker and Christ, Darth Vader and Satan. Even the original movie posters displayed a distinctly Renaissance Christian iconography with Luke and cruciform light saber forming the apex of the triune-triangle, Leia as Mary, the droids in a Johannine stance, and Vader pervades the background in a Fatherly role.

There’s something about Star Wars that triggers a variety of religious experiences, from sci-fi eager adolescent male to warrior evangelical. In part, this is because it participates in the ongoing process of remythologizing, or what I’ve elsewhere called a mythical mashup. Myths only last if they are retold and acted out through ritual, updated for a new day and age. An old story is mixed with a few other old stories as it is retold, repackaged, and repurposed, resulting in something both familiar but also brand new.

George Lucas and his film participate in such mythical mashings. At first look, Star Wars seemed wholly new even as we quickly recognize the elements of the story: damsel in distress, a young hero-to-be whose family is killed, wise elder, and some talkative sidekicks. Lucas right away gets the nuances of myth right, starting with the opening epigraph: “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away . . . ” which conjures up the ambiguous setting of so many lasting stories, of “Once upon a time, in an enchanted forest,” and “In the beginning . . .” All such stories, when well told, give us the time and place setting, but are likewise not so clear about it all: how long, exactly, is “a long time ago”? Ten thousand years? Or, maybe just ten minutes if you’re my daughter in the car running errands. At the same time, Lucas pushed the technology and computer-generated imagery in unheard of new ways, but he also continually came back to the decidedly low-tech: farmers in a desert clime, a jazz bar, meeting up with traveling merchants, and the interaction with other seemingly carbon-based life forms. A good myth has gotta be out of this world just as it is graspable in the here and now. There is a delicate balance of push and pull between familiar and strange that stands at the heart of good stories, and thus good myths.

Page 2 of 3 | Previous page | Next page