cannabis club

by Luís León

Counted among my pantheon of personal heroes while growing up in California’s East Bay area were Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong. I was a strange kid. I still sometimes mimic Cheech’s purposefully exaggerated Chicano accent, American English with a Spanish rhythm and Aztec intonation, also known as Calo or Mexican American “Spanglish.” Its a sound distinct to the borderlands experience; the echo of Aztlan: the Chicana/o mythical homeland; a sanctuary; a pipe dream. When I speak like Cheech to my close friend and academic colleague, who I affectionately call Chong, we deploy a linguistic code decipherable sometimes only by us, and perhaps a few other confidantes. Referring to four twenty, I often say “los santos,” or just santos, which translates loosely as “the saints.” We conspire in our devotion to them. Like the Rastafarians, the practice becomes a sacred ritual. For us, praying to the saints, our muertos, is an attempt to connect to the divine; a gestural offering in hopes of elevating our spirits to Elysium; the mythical land of the triumphantly dead, or physically displaced, the heavenly space where the souls of heroes dwell. Aztlan by another name. This, I believe, is how my Chicano hero, Cheech Marin, understands his devotion to los santos.

It’s appropriate that Cheech, a Mexican American, would open the artistic space for the popularization and promotion of marijuana into the soul of American popular culture. The word, la palabra, derives from a distinctly Mexican Spanish, with a folk etymology leading to original usage by a legendary diva, señora Maria Juana. The name resonates. Consider the thinly veiled celebration by the late funk sensation Rick James:

I love you Mary Jane, you’re my main thing,

you make me feel alright, you make my heart sing.

And when I’m feeling low, you come as no surprise,

fill me up with your love, take me to paradise.

But there are many names for marijuana; some call it “the Buddha,” others “Ganja,” “mojo,” “ju ju,” and other nomenclature signifying its spiritual import. And yet, its potential to induce a mystical experience has largely escaped the scholarly gaze of religious studies. The term marijuana came into American usage in 1873, plotted into one of Hubert Howe Bancroft’s racist manifestos, Native Races of the Pacific States. There he impugned Mexicans by attributing to them what he deemed barbaric rituals, including the smoking of herbs and roots for purposes of conjuring hallucinations and states of ecstasy. Bancroft was blinded by his racialized vision of civilization.

On the other hand, in 1910 William James claimed that any activity or substance that distracted a person’s fixed attention could open up the psychic terrain wherein mystical experiences unfold. Counted among the catalysts were alcohol and psychotropic drugs, which acted as portals to a spiritual place of fresh revelation. In 1932 Walter Benjamin wrote about his experiments with hashish, a concentrated form of marijuana. In his “Hashish in Marseilles,” he describes the sensations of watching himself from outside of his body: ecstasis. When walking the streets his senses are heightened; he is penetrated by the aromas, the sonic vibrations, the aesthetic assault of a hot day in a pleasantly crowded French city. “It was not far from the first café of the evening,” he proclaims, “in which, suddenly, the amorous joy dispensed by the contemplation of some fringes blown by the wind had convinced me that the hashish had begun to work.” Remarkably he and James (both Rick and William) agree: “And when I recall this state,” Benjamin concludes, “I should like to believe that the hashish persuades nature to permit us—for less egoistic purposes—that squandering of our existence that we know in love.”

The act of smoking cannabis is an erotic spirituality, a praxis initiated by intense sucking, with the goal of capturing the maximum amount of smoke, of inhaling deeply, pulling and holding the breath; testing the limit; spirit. And then there is the release; the small death, that rapturous moment marking the satisfaction and joy of surrender. That is the pivotal movement when the lungs and the heart rock, when pleasure breaches the limen between the sacred and the profane.

Exhaling, some can shape the billowy plume of smoke with their mouths into an ethereal art form.

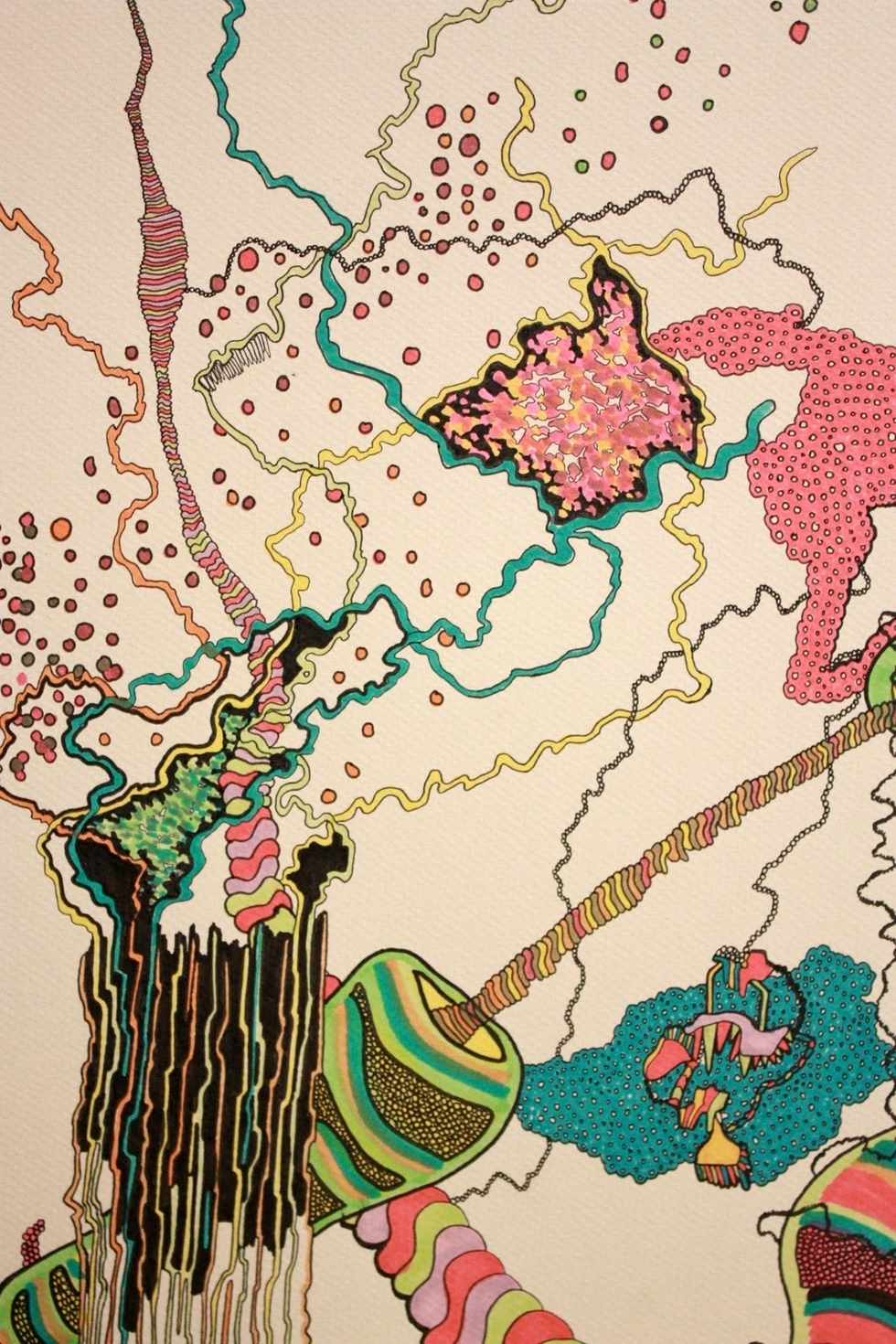

Indeed, marijuana is a gateway drug. Temporal borders seem to collapse as the act recalls the ancient sages who deemed the smoke sacred in its own right. Like the burning of copal, the cloud signals another state of consciousness, a liminal place where the psyche is permeable to fresh revelation. There, thoughts are intensified, scrambled, and reassembled into fragmented narratives that disrupt mundane cognition. Identity is questioned, challenged, opened, expanded. Though somewhat intellectual, that is the spiritual work.

So marijuana is medicine, at once traditional and modern. Today, sixteen states and our nation’s capital, the District of Columbia, have recognized its medicinal value and legalized medical marijuana. Hence, in states like my own, California and Colorado, pot production and consumption have created an epic artistic and spiritual awakening. The shift from an underground culture to a mainstream movement is transforming American society and architecture. A neighborhood in Oakland has been renamed “Oaksterdam” and is the site of the first American Cannabis college. Recently thousands jammed into the Colorado Events Center for the 2011 Cannabis Cup competition and expo. All across America dispensaries are sites of spirituality. New strains of marijuana (Purple Haze, Train Wreck, AK47, Blue Skies, Yellow Kush), new forms of distribution, and new information all contribute to the emergence of artistic and ritualistic communities. Dispensaries frequently hold events and those in California can offer areas to medicate, free food, television and movies, internet access, and games, providing a platform to experience shared rites and community—the communitas.

The dispensary is a liminal space wherein the spirituality of cannabis can implode and explode. Each time I experience the warm embrace of my dispensary, I bask in the light emanating from the freedom of religion we as Americans so pompously celebrate. This is my church. There I connect to a community of likeminded believers and practitioners. There I am confronted by the awe-inspiring miracle of marijuana cultivation and presentation, the dozens of strains each distinct in color, shape, texture, odor, and effect. I am dazzled by the narrative of mixed strains, and by the array of precise medicinal properties each boasts. How can my provider be so knowledgeable of this one sacred plant? And how can there be so much to know? He, my “caretaker,” is truly my priest, a master of the botanical arts, a holy alchemist of spiritual ecstasy. My offering seems the lesser of our ritual exchange; money is eclipsed by the weight of his gifts.

¡Viva la Revolución!