Brazilians are fond of saying that god is Brazilian. No other country in the world is blessed with so many natural wonders, gifted practitioners of the jogo bonito (the beautiful game–soccer), and a pervasive joie de vivre. This expression, however, has always been uttered with a heavy dose of irony, coupled with the affirmation that Brazil is the “country of the future and always will be.” In the face of recurring repressive, corrupt regimes, and persistent poverty, this future never seemed to arrive. Brazil always seemed to fail to live up to its potential.

Lately, things have changed. Brazil is now a stable democracy with an expanding urban middle class and one of the most dynamic economies in the world. With a blistering 7.5% growth rate, the country seems poised to surpass Britain and France to become the fifth largest economy of the world, and, in the process, to transition from a regional to a global power.

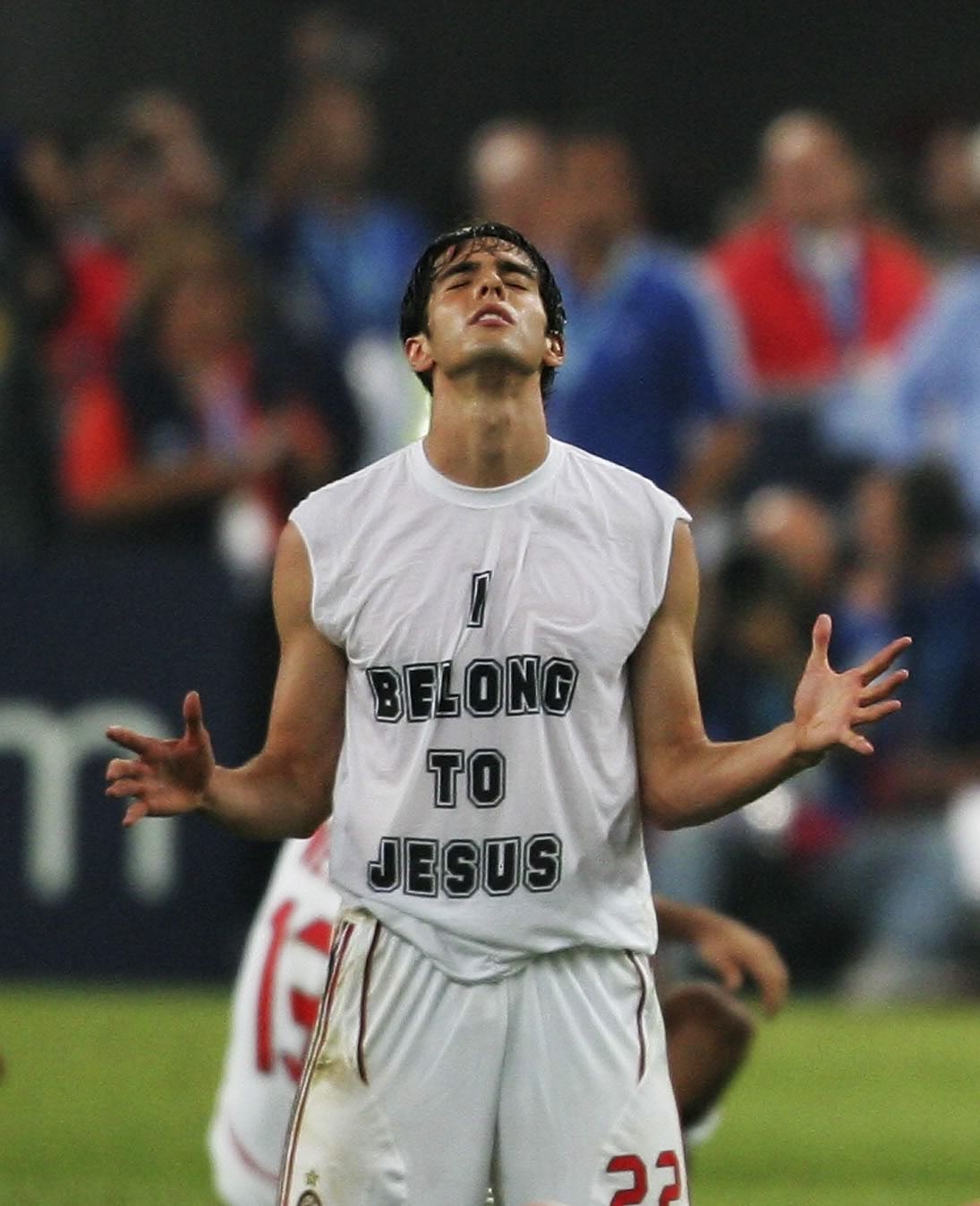

A central dimension of Brazil’s global projection is its vibrant and variegated religious field, which has become a key node in a new global cartography of religious production, circulation, and consumption. From “Neo-Pentecostal” churches that unabashedly espouse a prosperity gospel and resurgent African-based religions such as Candomblé and Umbanda to shamanistic religious movements that use psychoactive substances to induce altered states of consciousness, such as Santo Daime and União Vegetal, and spiritist mediums who conduct bloodless surgeries like John of God, Brazil is now at the cutting edge of a global “hyperanimism,” a transnational outpouring of the Spirit and/or spirits that is redefining the place of religion in late modernity.

This polymorphous global hyperanimism transgresses the colonial gaze that gave rise to the concept of animism in the first place. E. B. Tylor coined the term to characterize what he understood to be the most “primitive” form of religion, namely, the simple belief in spirits. Tylor argued that modern religions such as Christianity evolved from animism as societies and cultures became more complex. Present-day animism, however, is not some atavistic remnants of humanity’s past. Rather, this “New Animism,” as Graham Harvey calls it, is populated by a variety of vital and effective agentic forces that dwell not only in “nature” but in the commodities and images that we consume daily. Present-day animisms thrive by in-forming and using the advanced tools (such as global culture industries and electronic mass media) of a modernity that was supposed to have superseded religion through a relentless process of secularization and disenchantment.

Ever since the days of Aimee Sample McPherson, Pentecostalism has shown that it is particularly adept at bridging the local and global, the personal and universal, by blending popular culture, entertainment, glamor, the latest advances in media, and good old-fashioned face-to-face evangelization to perform the works of a deterritorialized and deterritorializing Holy Spirit. In competition with Nigerians, Ghanaians and, of course, Americans, Brazilians have elevated the performative dimensions of Pentecostalism several notches, contributing to the creation of a global pneumatic culture of the spectacle, a “charismatic corpothetics,” to draw from anthropologist Simon Coleman, that is disseminated globally through the Internet, TV, and DVDs and other religious paraphernalia.

Page 1 of 3 | Next page