Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (HVNP)

by Sally M. Promey

A placard posted near the Wahinekapu (“sacred women”) Steam Vents at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park locates the visitor on a map (“You Are Here”) and frames the viewing experience in scientific vocabulary: “This grassy landscape was once a part of a great volcanic collapse. About 500 years ago, during the growth of the Kilauea Volcano, a large summit collapse occurred. . . .” Two paragraphs into this geological discourse, the subject seamlessly shifts to declare the landscape spiritual terrain. A boldface subtitle announces that “Pelehonuamea (Pele)” is “Goddess of all things volcanic”; the text continues: “The mana (spiritual energy) of Pele is powerful, and her presence surrounds you. She is the lava rock you walk on, the glistening gold strands of volcanic glass in the cracks, and the breath of steam that engulfs you.” The final line of text names the land as “sacred” and then gently invokes “Hawaiian culture” as interpretive context: “Please be respectful of this sacred area and what it means to the Hawaiian culture by staying on park trails and by not littering the steam vents.” A nearby placard asserts “a Hawaiian landscape . . . is often a site of great spiritual significance.”

These two signs incorporate within themselves the general peculiarities of National Park Service (NPS) informational signage at HVNP: the signs include multiple registers of experience and information and seem to address scientific, scholarly, reverential, and devout audiences. The text moves from one to the other with less than a glimmer of acknowledgment. The NPS, the format suggests, is simply providing “information.” Here the information is of a scientific, “spiritual,” and regulatory sort and the audiences are presumably tourists of both natural and spiritual phenomena as well as Native Hawaiians concerned about stewardship of a landscape they consider sacred.

A bit farther down the Crater Rim Drive, the Thomas A. Jaggar Museum, opened in 1987, occupies the site immediately next door to the U.S. Geological Survey’s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, from which scientists study Hawaii’s volcanoes. The NPS website describes the work of the museum: “The Thomas A. Jaggar Museum is a museum on volcanology with displays of equipment used by scientists in the past to study the volcano, working seismographs, and an exhibit of clothing and gear from scientists who got a bit too close to lava.” Easily visible from the Jaggar’s outdoor viewing area, steam billows skyward from the active Halema’uma’u Crater in the larger Kilauea Caldera.

Official signage inside and outside the museum names the park’s acreage as the “land where the goddess dwells” and invites the visitor to “experience for yourself, the spirit with-in this awe inspiring wahi kapu” or “sacred landscape” of volcanic rock. One sentence acknowledges a cultural source for this interpretation but anticipates that contemporary visitors of any ethnicity or heritage will share a common response: “As you enter this wahi kapu, prepare to be inspired, for Native Hawaiians believe this to be the home of Pelehonuamea (Pele), the creator and creative energy that formed these volcanic islands.” The texts on these signs juxtapose multiple frames of reference within their own literal frames. Each placard carries the header “National Park Service/U.S. Department of the Interior” in its upper right-hand corner.

It is not the inclusion of information about ancient Hawaiian culture and religion that elicits my attention here—but rather the preference for the terms “spiritual” and “sacred,” the integration of the scientific and the spiritual, the NPS promotion of spiritual positioning and sensation within the visitor (“experience for yourself the spirit within….”; “prepare to be inspired”; “[Pele’s] presence surrounds you”), and the conflation of past and present moments in Hawaiian practice and “tradition” into one long, indistinguishable set of beliefs and behaviors. Science and spirituality become mutually reinforcing “truths.” The word “religion” is rarely if ever uttered. This is “spirituality.”It is “sacred,” it is Hawaiian culture—it is also natural.

At the Jaggar museum the “integration” of science and spirituality is the work of a team of NPS designers in collaboration with the artist Herb Kawainui Kane whose paintings of Hawaiian volcano gods, and especially Pele, shape the exhibition and signage. Greg Johnson, in his published research on a 1996-1997 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) case, reports on Kane’s participation in the hearings. In the course of his testimony, Kane self-identified as “part Hawaiian,” in the sense, he added, that “we’re all part Hawaiian these days”. In 1984, about two years prior to Kane’s selection by the NPS, the Pure Land Buddhist Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Honolulu celebrated him as a “living treasure of Hawaii,” perhaps informing the NPS’s invitation to participate on the Jaggar Museum exhibition design team. The museum displays Kane’s artwork, woven seamlessly into its educational programme and NPS gift shops sell reproductions of Kane’s paintings as well as his book on Pele, a work “inspired by” the museum design assignment.

Here and elsewhere, in the Hawaiian Islands and among other “native” populations, the U.S. National Park Service puts “spirituality” explicitly into formal circulation. In this process, this most porous of “religious” categories accomplishes substantial work. Scripting a range of behaviors and sensations at Kilauea’s rim and in the caldera, it simultaneously frames, protects, invites, discourages, and facilitates “spiritual expression” of various sorts.

Agreement about this spirituality of place is shared by at least some park employees and visitors at HVNP. On the day of my recent visit, for example, on hearing of my interest in the public display of religion, one park ranger volunteered that he settled there in part to learn spiritual lessons from “native Hawaiians” and that he consequently belongs to a nearby Hawaiian language Christian church choir. He recommended that I stop to hear self-described “Praise and Worship leader” Rupert Tripp, Jr. who was singing at the main Kilauea Visitor Center. According to his web-pages, Tripp lives in Volcano, HI, and writes and records “music of the heart” “for the glory of my Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.” When I went to listen, the musician had gone on break, but the literature he left on his table, including a flyer on NPS letterhead, identified his performance as part of a “series of Hawaiian cultural programs sponsored by HVNP and Hawaii Natural History Association.”

At the Jaggar Museum, furthermore, two practitioners of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, perhaps responding to the “spiritual” license of the place, set up their table of pamphlets near the main entrance to the museum and observation deck. No one on site the day of my visit recommended music of any other sort or offered literatures disconnected from the place’s spiritual performances. The NPS’s official embrace, even promotion, of the “spirituality” of this place apparently sets in motion its selection for the exercise of religious freedoms protected by the first amendment to the Constitution of the United States. The volcanic landscape, and the NPS characterization of it in its signage, did not specifically anticipate Rupert Tripp or the Jehovah’s Witness literature arrayed on a table in the sun at the Jaggar Museum’s entrance gate. The NPS did, however, script the possibility of such performances into its signage.

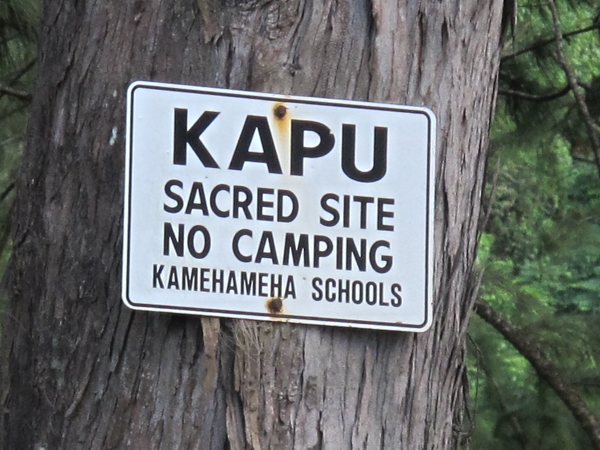

Spirituality, in its very fluidity, can be also constraining and regulatory. The NPS designation of HVNP as “wahi kapu,” attended by their translation of the term as “sacred landscape,” provides an interpretive frame for another sort of Big Island signage beyond the park’s borders. Invariably the first and largest word on these sometimes manufactured, sometimes hand-lettered signs is an uppercase “KAPU.” Often, but not always, the signs mark national, state, or local government property, sites of significance for Hawaiians who claim descent from ancient island ancestors. “Kapu” here signals the borders—and thus fixes the boundaries—of contested spaces, contested ethnic and religious “properties.” These “sacred” spaces display literal “no trespassing” signs that carry with them a touch of the mortal threat of ancient Hawaiian religious systems where, tourist guides repeatedly remind visitors, “kapu” also meant “taboo” and the penalty for violation was frequently death.

At HVNP an important chapter in this story concerns just what it is that makes “kapu” this particular “wahi” and how this translates elsewhere on the islands. As the official signage maintains: “The mana (spiritual energy) of Pele is powerful, and her presence surrounds you. She is the lava rock you walk on . . . “ In this rendition, the earth, the rock, is the goddess Pele, it is simultaneously her body, her creation, her residence, her possession. “Living” lava, molten volcanic stone, shapes a world in the process of coming into being, the result of Pele’s creative activity. The landscape and, by commonly invoked synecdoche, the stones that constitute the landscape hold the power and “memory” of creation and its connection to Native Hawaiian divinity. In this scenario, individual stones become circumscribable pieces of the spiritualities of the land. At HVNP, material offerings to Pele authenticate the designation of the landscape, and the stones in particular, as “kapu” and as manifestation of this particular deity.

The most common sort of Pele offering, the Ti-bundle, is simply composed: a lava rock wrapped in a leaf of the Ti plant. Other plant matter, flowers, or small objects may be tucked into the bundle or set beside it; all that is necessary, however, is a lava rock and a single Ti leaf. The ritual involves selecting the rock, making a petition, wish, or expression of gratitude, wrapping the rock with Ti to “contain” the petition and enhance its efficacy, and placing it at a spiritually auspicious site, such as near ancient petroglyphs, at a heiau (temple), on a grave site, or at some identifiable threshold of an active caldera, crater, or steam vent. On the well-marked four-mile HVNP Kilauea Iki Trail, a pyramid of lava rocks, at precisely the point of entry into the active caldera itself, has accumulated many such offerings. The varying degrees of desiccation of the Ti-leaf wrappings suggest that petitioners have left the bundles over an extended period and at different times.

Polynesian Ti grows plentifully in Hawaiian gardens and in the wild and supports many common uses. These have included rain capes and coverings, shelter thatching, food wrappings, and skirts. Ti is also the preferred ingredient in certain healing practices and in the production of offerings and leis. The plants, and especially their large, smooth, long leaves, are widely considered to dispel evil and bring good fortune. Perhaps because of their long association with divine power, with protection as well as decoration, Ti plants often grow around the perimeter of Hawaiian homes, Christian churches, Buddhist temples, and burial grounds.

Of at least passing interest here is the fact that some HVNP rangers claim authority to separate “authentic” from “inauthentic” Pele offerings and to remove those they deem inauthentic. In the case of the ranger who volunteered this information, those that require removal are made with soda or alcohol cans and bottles rather than the “natural” material of lava rock. Since rangers rarely witness the actual leaving of offerings, they cannot effectively monitor that aspect of this ritual process. Instead, at HVNP, rangers base their assessment of authenticity solely on appearance and materials of the Ti-bundle, lei, or other gift. In my day at the park I did not see a single offering employing these commercial materials, though I saw many of them at sites outside the park. At Maui’s Haleakala National Park, on the other hand, I was told by a NPS ranger that it is official Haleakala policy to remove all offerings because any object that introduces plant material from one ecological zone to another may also introduce insects and diseases.

That Pele and other ancient gods sustain contemporary connections to stones and rocks informs the proliferation of “Hawaiian” stories that take the powers of stone as their subject. Some of these narratives concern ancient histories and spiritualities, some concern the miraculous feats of Kamehameha I and other Hawaiian royalty, some concern current convictions about such lithic objects as Oahu’s so-called “wizard stones” or “Stones of Life” (re)installed, on a lava rock platform with a new lava rock altar, near the beach at one end of Waikiki by the Department of Parks and Recreation of the City and County of Honolulu in 1997. These stones purportedly contain spiritual powers invested in them centuries ago by four powerful ancient Tahitian kahunas or healers. On the day of my visit there, someone had left a lei offering.

Among the most widely circulated contemporary articulations of the “spiritual” power of Hawaii’s volcanic stones is the description of Pele’s curse. According to this tradition, anyone who removes a volcanic stone (a part of the goddess herself, or her creative “property”) from the islands invites bad luck. The sources of information about the curse are many. Tourist guidebooks are first among the media that prepare travelers to face with some trepidation the potential acquisition of a lava rock souvenir. HVNP receives many packages of lava rocks each year, returned by travelers from abroad, hoping good fortune will ensue if they send Pele’s stones back to Hawaii. Volcano Gallery, a division of Rainbow Moon, in Volcano, HI, has made an enterprise of lava rock return, an activity that might be interpreted as a kind of goddess “repatriation.” Volcano Gallery’s website tells beleaguered travelers how to return volcanic rocks to Rainbow Moon which promises to perform appropriate rituals on the former tourist’s behalf. Specifically, employees of Rainbow Moon will make each rock an offering to Pele. They will wrap the rock in a Ti leaf for good luck, place the bundle in a respectful location “close to the home of Pele,” and add an orchid, a petition for the goddess’s “forgiveness.” This distinguishes them, Rainbow Moon reports, from HVNP, whose employees will simply toss returned rocks on a pile of similar objects behind the Visitor’s Center. For their ritual service, Rainbow Moon welcomes voluntary donations of $15.00. They also invite their clients to send testimonies, which have, over time, facilitated the assembly of an archive of lava rock stories. This site, and the information it disseminates, contributes to the choreography, and economy, of spiritual performance at HVNP and elsewhere in the islands.

This short essay has taken as its subjects volcanic stones and the various “spirits” understood to permeate them, lava rocks and the sacred” landscapes they constitute, as well as the deployment of spiritualities concerning these objects and places by the NPS and other Hawaiian agencies or agents. The work accomplished in this latter maneuver, and especially by the NPS, is multiple and various, situated against the backdrop of immensely complex histories of American imperialisms (political, religious, cultural, commercial). Against this backdrop, NPS parsing of the spiritual calls into the conversation issues of possession, questions about whose gods, whose spirits, whose interests are in this land. In ceding ground to Pele, the NPS acknowledges Hawaiian “spiritual” ownership of the land. It also appeases possible complainants and wards off litigation in a period of amplified native claims and Hawaiian nationalist activism.

This land is spiritual, the NPS signage declares—and its spirituality is “Hawaiian.” But this signage, the “property” of the United States Department of the Interior, also claims custodial authority of the land, and its native Hawaiian spiritualities, for the United States. As custodian, the NPS officially suggests, imposes, an attitude of reverence on the part of tourists and visitors, mandating the appropriate mode of approach to the “soul” of these things and places. This is an “off-limits,” or kapu mandate that requires specific behaviors, a zone of respect with which no reasonably minded person can quibble. In “one fell swoop,” the NPS offers, and asserts, connection and atonement as well as appropriation.

Spiritual ownership, the United States government knows from historical practice, is not about actual possession or property—spiritual ownership is a qualified ownership falling “outside” of a capitalist land economy. In narrating “spirituality” rather than religion, the NPS manages to carefully orchestrate its implicit packaging of property rights. Spiritual ownership by one party coexists with property ownership by another.

The spiritual uses of objects and the land here also accomplish one additional noteworthy task. In evoking Hawaiian “spiritualities” rather than Hawaiian “religions,” the NPS and other agencies make public space for the “religious” in the “secular” state. Rupert Tripp and the Jehovah’s Witnesses apparently recognized this on the April day of my recent visit to HVNP. If secular society exiles “religion” to the individual interior, shaping our understandings of the spiritual in accordance with this presumably inviolable (and politically silenced) interiority, “spirituality” also often escapes these boundaries and operates without these constraints. At HVNP, it manifests, formally and officially, as an under-the-radar assertion of the United States (and its “possessions”) as “one nation under God(s).”