The Church of William Blake

by Thomas Csordas

Having been intrigued by William Blake’s celebration of imagination as the wellspring of poetry and prophecy since my introduction to his Songs of Innocence and Experience in high school, I was elated when in the final term of my senior year in college I had the opportunity to take a course completely devoted to Blake’s work pass-fail. Midway through the term, our professor made an announcement that he had received notification of a kind of pageant based on the work of Blake that was to be held in the hills outside the not-too-distant college town of Athens, Ohio. I decided to attend, and convinced a friend to come along.

The event had the cryptic title “Hail the Depth of the Skin.” It took me many seasons to conclude that this was a contrarian response to the old saw “beauty is only skin deep.” The pageant was being staged by a group called “The Church of William Blake,” which proved to be not only a church but also an artists’ colony, organized under the charismatic leadership of Æthelred Eldridge (whose day job is as an art professor at Ohio University). It was located on Eldridge’s property near Mount Nebo, which is the highest elevation in Athens County and is endowed with a particularly dense spiritual history. It is reputed to have been sacred to the Shawnee, renowned as a center of Spiritualist activity in the mid-1800s, widely understood to be haunted by a diversity of spirits, and possibly, situated at the intersection of magnetic lay-lines. Eldridge calls the place Golgonooza, which is Blake’s name for what we might call a city of humanly rather than heavenly imagination, a city of creativity and ebullience, a contrarian version of what more conventional and conservative cults might refer to as a New Jerusalem.

Given our mood of anticipation, finding Golgonooza in the hills outside Athens was an adventure in itself, but it was evident when we arrived that we were in the right place. Slightly off the road, nestled in a pasture among the verdant hills, a large log stage with a podium—more properly a pulpit—had been constructed, evidently just for the performance of “Hail the Depth of the Skin.” It appeared as though the woods had been crawling with hippie artists, all of whom had emerged from the foliage to converge on the pasture. Figures carrying large cardboard cutouts of the sense organs—eye, nose ear, tongue, lips, and genitals—moved all over the stage and throughout the audience as they took turns making prophetic pronouncements. All the while Æthelred Eldridge was declaiming from a pulpit in the style of an eighteenth-century Methodist minister, but rather than ascetic restraint from the Bible he preached imaginative excess and saturation of the senses from Blake’s epic Milton. When the pageant was over the hippie artists vanished again, leaving us to our dark drive home with afterimages of the event dancing in our heads…

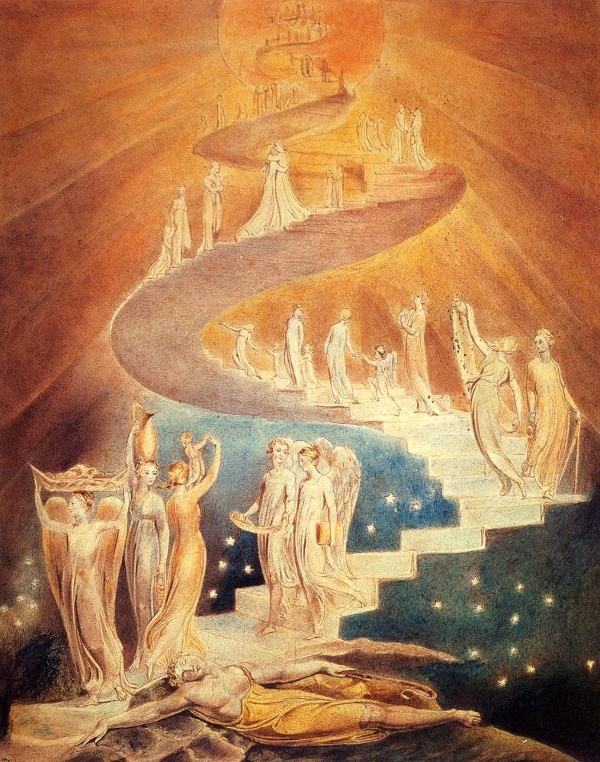

Blake was a visual artist—quite literally a visionary—as well as a poet. His engravings are as bold, powerful, and colorful as are his lyrical and prophetic works, and in those works in which the action of the text is accompanied by images of his mythic/heroic characters one can almost see an foreshadowing of Marvel Comics. The religious impulse in Blake is rooted in a celebration of imagination, bodies, and senses, as well as equality of the sexes matched in passion and creativity. He derided established religion as anti-imaginative, a position which for me has always been epitomized in the following passage from “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell”:

The ancient Poets animated all sensible objects with Gods or Geniuses, calling them by the names and adorning them with the properties of woods, rivers, mountains, lakes, cities, nations, and whatever their enlarged and numerous senses could perceive. And particularly they studied the genius of each city and country, placing it under its mental deity; Till a system was formed, which some took advantage of, and enslaved the vulgar by attempting to realize or abstract the mental deities from their objects: thus began Priesthood; Choosing the forms of worship from poetic tales. And at length they pronounced that the Gods had ordered such things. Thus men forgot that All deities reside in the Human breast.

Blake’s theory is one of poetic and corporal bringing-to-life made possible by the “enlarged and numerous senses” of the restored prelapsarian moment. For Blake the biblical myth of the Fall is a flight from concreteness to abstraction and the slavery of mystification. Forgetting that all deities reside in the human breast is for Blake equivalent to saying that the “binding” achieved by religion is the binding off of human imagination. Blake’s manifesto is thick with meaning, one strand having to do with the already braided historical-existential origin of religion, another having to do with the apparent “interiority” implied by the residence of deities in the human breast, and yet another having to do with the humanism in the poet’s—and the scholar’s—skeptical stance toward religion.

In the university course I was taking on Blake I learned that a number of people had undertaken to set various of Blake’s works to music. These included our own professor, Tom Mitchell, and before him Allen Ginsberg and Benjamin Britten. Sometime during the term I decided to do the same. The idea became a project of the kind that takes on a life of its own. So, having composed about a dozen melodies it became obvious that it made sense to perform them. Having decided to perform them it seemed that something more was needed, so I added a dramatic presentation of Blake’s poem “The Mental Traveler” as an opening. Having become the Mental Traveler, I required the appropriate garb, and so acquired a heavy cape and a walking staff.

There was still one more phase ahead in this imaginative transformation, however. All the performances I gave in the following years were in the role of “actor and musician” except for one, arranged when I contacted Æthelred Eldridge and offered to visit the Church of William Blake as “guest preacher.” Eldridge accepted my offer and we agreed that I would come to Ohio on a Sunday in February.

It was cold and snowy, the narrow, winding roads around Mt. Nebo were slippery, and I was late. When I arrived I heard Eldridge’s voice from within the one room log church. They had begun without me, not knowing whether the stranger from elsewhere would actually appear. It was the one time in my life when I calculatedly made an Entrance. In character and outfitted as The Mental Traveler, I knocked on the wooden door with my staff, and it became silent inside. Ætheldred Eldridge opened the door and questioningly said my name: “Tom?” I did not speak but strode past him, put down my guitar case and launched into the opening monologue. My intent was to produce the actual effect of a visitation by an unfamiliar Mental Traveler who talked about his journey through “A land of men, and women, too” in which the sexes both thrive and suffer on one another’s account as the generations revolve from youth to age. The performance went well.

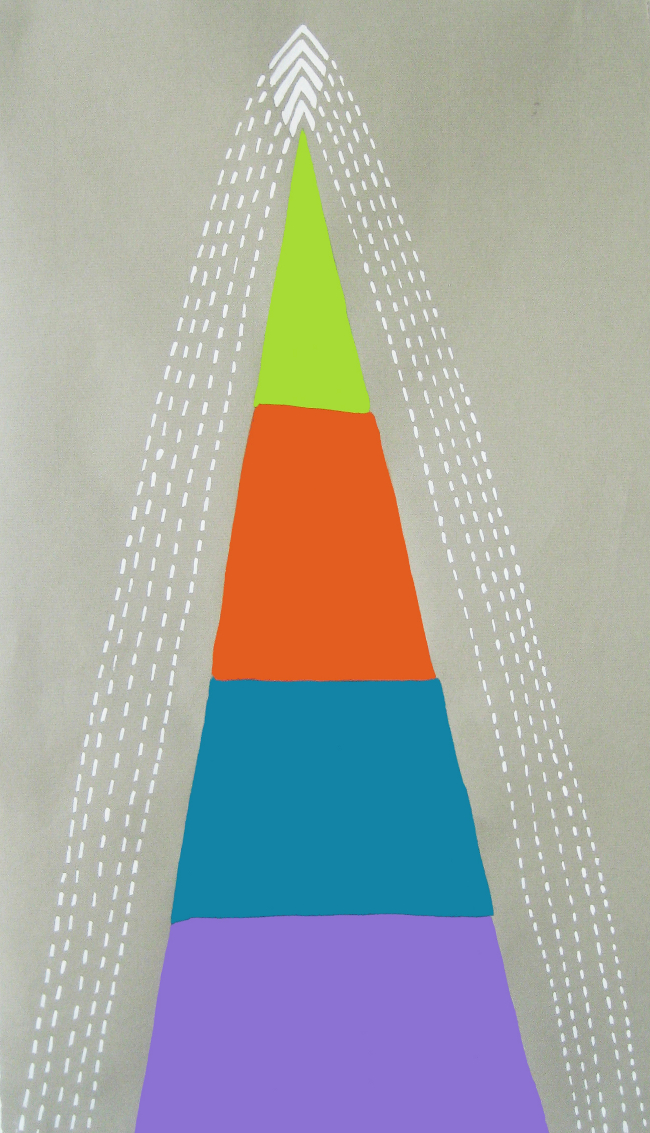

The role of visiting preacher suited me well. The Church of William Blake was a real church within a colony of artists whose members were “playing church,” where play and creativity were taken quite simultaneously with great seriousness and with tongue in cheek. The Sunday services were organized around texts read aloud from Blake’s collected works. In addition to the church, the main buildings in Golgonooza were a substantial log house and a printery/book bindery. Some inhabitants of Golgonooza lived in partially refurbished log cabins built by settlers in the early nineteenth century. Eldridge, as leader of the church and contemporary avatar of the spirit which has reputedly animated Milton, Blake, and Ginsberg, has produced both visual and verbal art. His works include paintings which are as visually compelling as are those of Blake. His poetic manifesto is entitled Albion Awake, where Albion is Blake’s term not only for Britain but for the slumbering creative potential of humanity as a whole. It’s a vision worth celebrating.