Star Wars

by S. Brent Plate

At ten years of age I walked onto a large, grassy field at Colorado State University where the kids in my summer camp were already playing. A few of them recognized me from previous years and ran up to greet me. Strangely, they did not say, “Hello, how are you?” Rather, they opened our summer with a direct inquiry that challenged my coolness: “Have you seen Star Wars yet?!”

It always sucks to be the last one in on something, and I had to confess that I had no idea what they were talking about. My friends began to explain how there were lasers and spaceships and a really bad guy named “Death Invader” or some such. Before long, one of the camp leaders came over and he too began excitedly trying to explain the film to me. It sounded like the strangest, most mysterious, magical thing I could imagine.

I immediately went home and convinced my mother of the dire magnitude of the situation. By the time I actually saw the movie a few days later, I had the key names memorized, and had a working familiarity with the “death star” space station and something about a “life saver” laser sword. I learned this without McDonalds franchising. Now, thirtysomething years later my six-year-old daughter has her own plastic light saber, a Clone Wars lunchbox, and a Lego® Echo Base Station. She can also talk a good Wookie. All this knowledge even though she’s never seen any of the films. We’ve become so much more efficient at acquiring our mythologies in the thirty-five years since the original.

The Auratic Galactic

Star Wars proves that Walter Benjamin might have been wrong when he argued that the aura of art withers when artworks are mass reproduced. Benjamin’s idea was that artworks (particularly those before photography and film) could possess a presence that was seemingly natural despite its socially constructed setting. There’s only one Mona Lisa, only one leaning tower of Pisa, and people travel to bask in the particular space and time of their highly charged presence. For Benjamin, the power of this locatable “authenticity” was not so much intrinsic to a unique artwork, but was created through collective, social feeling. This was often evoked through ritual, pulling viewers toward that feeling from great distances.

Film was supposed to change all that, as feature films would arrive “at a theater near you.” The unique, authentic appearance of the work of art was dispersed across theaters, throughout time and space, and thus an aura could not surround one singular, unique, separate work. The journey was now proximate, and mass distributed. What authenticity was there in that?

Films like Star Wars confirm that some semblance of an aura is alive and well in this dispersed, postmodern, postindustrial world. These films tell us something too about our ongoing desire for the sacred mysteries and ritualistic events that, increasingly, have been fulfilled by mass media for masses of people. Here, even when a film is shown and watched in theaters around the world (i.e., there is no “one” Star Wars) an aura has been established around some seemingly single work of art, at least one that many people can collectively discuss. Each of us hundred million or so who have seen the original or sequel Star Wars films in our own places and times, respond, react, and register our own likes and dislikes across continents and generations.

When new installments of the Star Wars series have been released, thousands of people in all corners of the globe have set up camp for days at a time outside the box office waiting for tickets to go on sale, dressing in appropriate costumes, and speaking in intergalactic lingo to their fellow fans camped out alongside them, and basically having a good time in their neo-rituals. Others plan for Star Wars theme weddings and bar mitzvoth (like Mark Zuckerberg). And when the 2001 Australian national census resulted in 70,000+ people marking “Jedi” as their religion, Chris Brennan, director of the Star Wars Appreciation Society of Australia, responded, “This was a way for people to say, ‘I want to be part of a movie universe I love so much.'” Fans declare their allegiance to an alternate reality, one posited to be in contradistinction to mechanically reproducible office cubicles, mortgage installments, and traffic commutes. The mass distribution of Star Wars does nothing to diminish its aura—if anything, it offers a new terrain to diagnose the sacred and profane of their postindustrial lives.

Mythical Mashup

The “camp” where the Star Wars aura began for me in the summer of ’77 was really a two-week babysitter as our parents attended talks and sessions as part of “staff training.” This was the annual gathering of Campus Crusade for Christ staff members from around the world. In other words, my primal cinematic experience occurred in the midst of a bastion of a budding brand of evangelicalism, just then filtering across the country. Many of these evangelicals had been to the conservative-Christianity-meets-pop-culture event called Explo ’72. Many of them were interested in the “born-again” Democrat Jimmy Carter, then in office, but had yet to fall under the spell of thespian-evangelical trickster, Ronald Reagan.

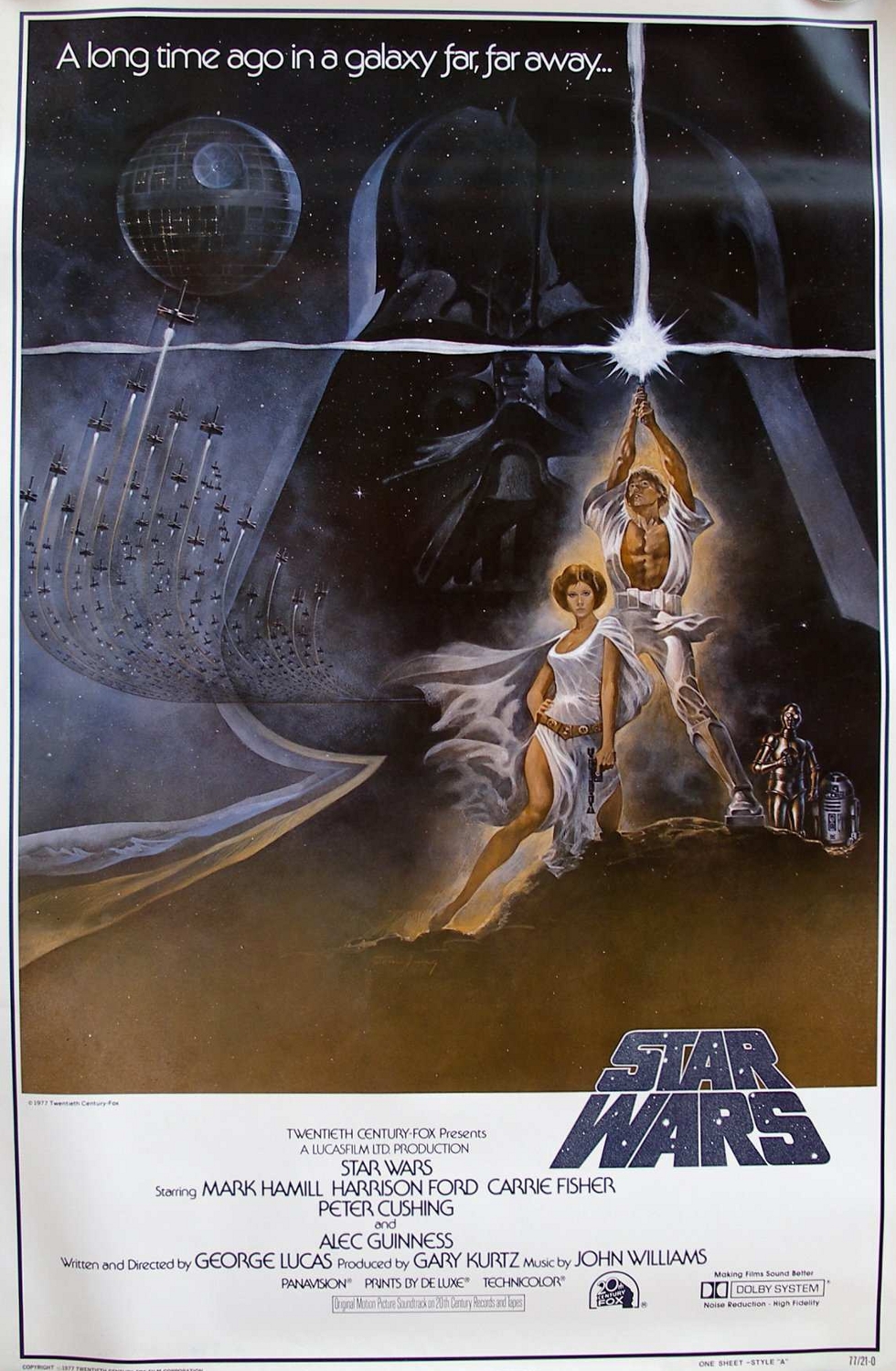

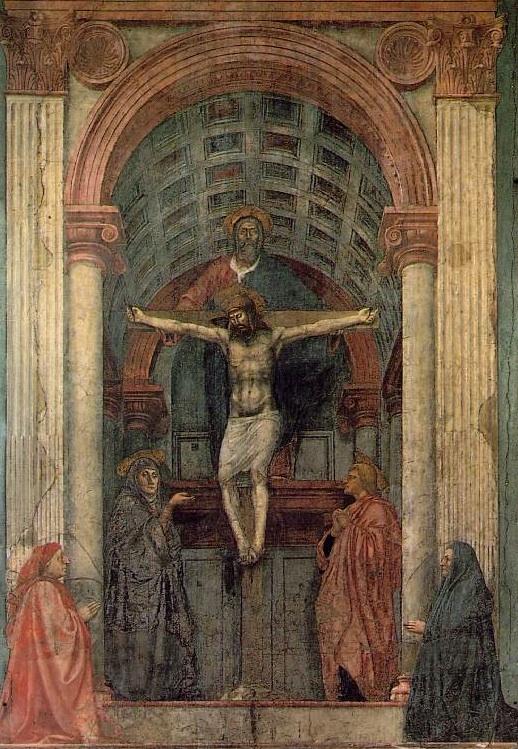

Nobody seemed to care much about the potential theo-politics of Star Wars. Only a few seemed to identify usable theology in it. Some deployed the film to repeat Christian-sounding messages (The Force is God), or to capitalize on the mythic parallels between Obi-Wan and John the Baptist, Luke Skywalker and Christ, Darth Vader and Satan. Even the original movie posters displayed a distinctly Renaissance Christian iconography with Luke and cruciform light saber forming the apex of the triune-triangle, Leia as Mary, the droids in a Johannine stance, and Vader pervades the background in a Fatherly role.

There’s something about Star Wars that triggers a variety of religious experiences, from sci-fi eager adolescent male to warrior evangelical. In part, this is because it participates in the ongoing process of remythologizing, or what I’ve elsewhere called a mythical mashup. Myths only last if they are retold and acted out through ritual, updated for a new day and age. An old story is mixed with a few other old stories as it is retold, repackaged, and repurposed, resulting in something both familiar but also brand new.

George Lucas and his film participate in such mythical mashings. At first look, Star Wars seemed wholly new even as we quickly recognize the elements of the story: damsel in distress, a young hero-to-be whose family is killed, wise elder, and some talkative sidekicks. Lucas right away gets the nuances of myth right, starting with the opening epigraph: “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away . . . ” which conjures up the ambiguous setting of so many lasting stories, of “Once upon a time, in an enchanted forest,” and “In the beginning . . .” All such stories, when well told, give us the time and place setting, but are likewise not so clear about it all: how long, exactly, is “a long time ago”? Ten thousand years? Or, maybe just ten minutes if you’re my daughter in the car running errands. At the same time, Lucas pushed the technology and computer-generated imagery in unheard of new ways, but he also continually came back to the decidedly low-tech: farmers in a desert clime, a jazz bar, meeting up with traveling merchants, and the interaction with other seemingly carbon-based life forms. A good myth has gotta be out of this world just as it is graspable in the here and now. There is a delicate balance of push and pull between familiar and strange that stands at the heart of good stories, and thus good myths.

In turn, the new mashup then takes its place within cultural tradition, becoming part of the mythical storehouse that we collectively cull from in the ongoing religious processes of world making. That the Star Wars films have become so firmly embedded in the U.S. mythological fabric is evident in a variety of venues. With the emergence of The Phantom Menace (“Episode I”) in 1999, the conservative Christian publication The World ran a cover story and follow up essays looking slightly askew at the “spirituality” of George Lucas, and the relations of the films to political, cultural, and religious life today. Meanwhile, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum ran an exhibition, “Star Wars: The Magic of Myth,” confirming the importance of inspiring hero myths as a subject of cultural science. In its displays, the Smithsonian tracked how the Star Wars films have been able to construct origin stories for young aspiring astronauts, space travelers, and the like. Along the way, books by respectable publishers bear titles like: Star Wars and Philosophy, The Dharma of Star Wars, The Tao of Star Wars, Star Wars Jesus: A Spiritual Commentary on the Reality of the Force, and The Gospel According to Star Wars. Cultural, religious, and philosophical works have drawn on the power of the films to make connections with the lives of people in the here and now.

One example makes the point particularly clear. Sal Paolantonio’s book, How Football Explains America, discusses how that sport creates a uniquely United States mythology. Quarterbacks, the ESPN correspondent says, are heroes in the classical sense. But rather than using, say, Perseus or Heracles as points of comparison, he says quarterbacks are heroes because they are like Luke Skywalker. Thirty years ago some critics and scholars were at pains to show how Luke Skywalker embodied the hero myth. Now, Luke Skywalker simply becomes a hero. Popular culture has become mythic certitude. The aura has become incorporated.

To this day, I can talk with people roughly my age and we can recount where we were (and thus, say something about who we were) on the summer of Star Wars, thirty-five years ago now. A twinkle emerges in our eyes as we talk about “our firsts” with regard the film, a remembrance of things past: the fresh sounds of swooshing light sabers, the bright colored laser beams, James Earl Jones’ voice as Darth Vader, Leia’s hair buns, a young Harrison Ford’s cheeky rejoinders. It is a civil mythology for a civil religious culture.