icon

by David Morgan

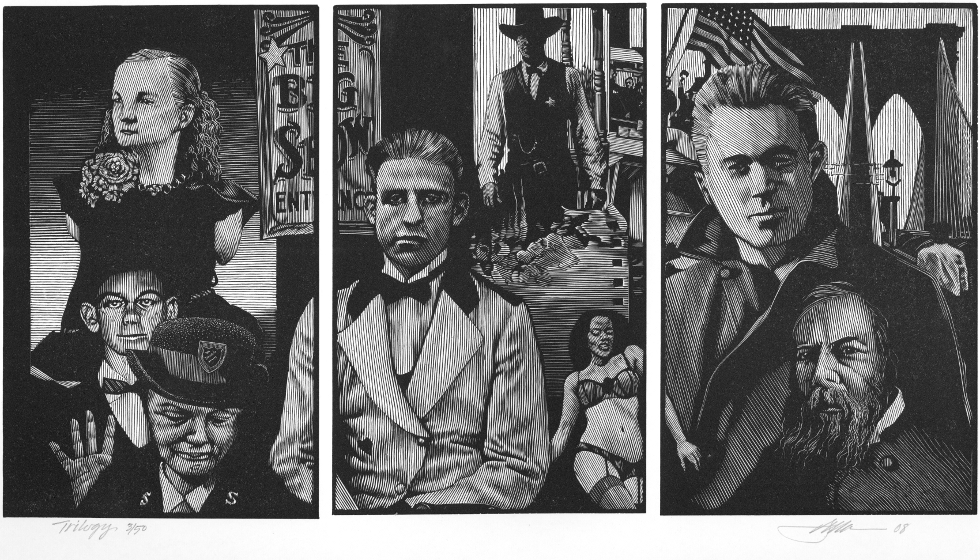

If there is meaning to the term “visual culture,” it is the webs of connection organized by images. Some images are special—they stand like mountaintops in a society, managing the flow of thought and feeling that constitutes the body of a culture. The word for this class of imagery is icon. You know an icon when you see one because of the auratic sensation it provokes: gazing at it, you are in the presence of something or someone widely revered or reviled. It’s not merely an image, a visual sign, but more. What you see in an icon is archetypal, totemic, paradigmatic, universally recognized. What you see are the edges of a life-world because whoever does not recognize the image as an icon must be an outsider or a foreigner or an unbeliever. The proof of an image’s iconicity is the aura it radiates—the sensation of the image grasping and holding your attention. I’d like to reflect on iconic aura because I believe it can tell us something important about the visual culture of spirituality.

Images of John Lennon, Marilyn Monroe, Che Guevara, Jesus, and the most familiar pictures by Norman Rockwell all command attention because viewers recognize in them something that they and many others want to see. These are icons, the images everyone talks about, images that seem to be everywhere and always have been. Take Rockwell’s undisputed “popular culture icon,” as it is so commonly tagged, “Freedom from Want,” painted in 1943 as one of a series of four images inspired by a war-time speech of Franklin Roosevelt. Why is it an icon?

Several reasons come to mind. First, we have seen it so many times. “We”—it’s not a private image, but one shared by millions of people who experience something common in their recognition of this image. The image bestows on people an imagined sense of their Americanness, as do many of Rockwell’s pictures. Second, its ubiquity: we see it every Thanksgiving in magazines and newspapers, on television and the Internet. When Rockwell created the picture it was not an icon of Thanksgiving, but a propagandistic hymn to the way things ought to be and would be once again when Totalitarianism was defeated on the global stage. Roosevelt defined the “freedom from want” in terms of economic relations that “will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants—everywhere in the world.” After the war, in the heyday of American plenty, Rockwell’s image was recoded and became closely associated with Thanksgiving, the American high holy day of Abundance, the feast day of American civil religion. We see no religious subject per se. Rather than Puritans or Pilgrims, we witness something more generic: the meal that all Americans celebrate. This points to the third feature of Rockwell’s icon—content and style. The image presents to people what they want to see—Thanksgiving as it ought to be, grounded in warmth and sentiment, in fellowship, in good cheer, in a ritual meal served up by two pillars of benevolence: grandmother and grandfather. And the scene is limned with the skill of an illustrator’s descriptive line and a composition that lures the eye and rewards it with balance and order, all packaged with the tidiness of a fine story. In his most fondly received works, Rockwell portrays the American past with a narrative gaze that interweaves humor, wit, nostalgia, and storytelling. Or maybe it’s not the past so much as a folkloric invocation of America as it should have been.

Ironically, what you see in “Freedom from Want” is what you want, which is to say, what you don’t have, which the picture promises to deliver. Aura is the substance of iconicity, the promise that beholding offers. Like a fragrance, it tantalizes. An icon exerts allure by revealing something of what viewers seek, but not everything. Icons open the door to the person or quality we want to hold. They modulate desire, direct the traffic of yearning. We see the picture of John Lennon and recognize him as the guy on whom the eyes of millions reside, in whom an age found its leader, spokesman, prophet, the hero we adore, the writer of songs that changed your life and the lives of millions. Or we look at a picture of Hitler and recognize with a shudder the maniacal evil that is uneasily, demonically fascinating. Icons bring us into the presence of the one and only, what we take to be the bedrock, the Real. In contrast to Plato’s insistence that images could not bear the Real, the icon does precisely that, indeed, it is only in the icon that the Real becomes accessible. The Real is not the actual. It is what seems to become actual in the icon, and only there. Something streams or radiates from icons. They hemorrhage uniqueness, leak the fluid of absoluteness, which is what I mean by aura.

But we need to say more about what aura is and how it constitutes the spiritual power of icons. An image has aura when we can’t ignore it, when it commands our attention. We say “That is Che Guevara” or “There is Marilyn Monroe.” The image captures the idea of the person, or the ideal, one might say. We behold the moment that changed history, as in the photograph of the raising of the flag over Iwo Jima. We behold the face of the ideal of feminine beauty in Marilyn or the face of the hero adored throughout Latin America in Che. Note in each example that it is not the ordinary we look for in the icon. We want the extraordinary. Icons are a visual strategy for securing the really real. We do not want Norma Jeane Mortenson, but Marilyn the goddess. We do not want Che the impatient and naïve ideologue, but the Latin Apollo and Romantic visionary. We want the Idea that animated the individual, that indwelled in her or him. In effect, we want an embodiment of what is otherwise invisible and inaccessible—we want something mythical or archetypal. Seeing icons is a visual practice of producing the Real as visible. The power of images consists of their ability to show the Real. In fact, rather than a Platonic gaze on eternal forms, the icon is a construction of the Real. After all, the photo at Iwo Jima was posed. Che Guevara practiced the execution of political opponents. Norma Jeane was a deeply unhappy, drug-addicted woman. An icon distills a singular idea of the subject from the complexity and accident of an individual person. More than the actual person it pictures, an icon is about the desire that its viewers bring to it. In some cases, the person may be virtually eclipsed by his icon. Is the particularity of a man named Jesus of Nazareth visible in pictures of Jesus the Christ featuring the authorized conceptions of his messianic mission and divine nature? Historians argue over his participles while believers seek the salvator mundi. Most of my Thanksgiving dinners aren’t as gleeful as the family feast in Rockwell’s icon.

Desire for what we do not have distinguishes the icon as a way of seeing. Beholding an icon without the desire that animates the devotee’s experience results in seeing a stereotype or a truism. Other people’s icons are just that to us, as alien as other people’s religions. If you don’t want what the icon offers, you see a cliché, not the truth. Your icon, by contrast, captures the essence of someone or something that you want. The aura of that elusive reality may be called spiritual, that is, the evocation of the Real. This truth is not discerned as the validity of a proposition, but is experienced as a sensation—the feeling of seeing the real thing. Radiated by an icon, aura is the sensation of the revelation of the authentic. Spirituality and desire are inseparable. “That’s it!” or “That’s her!” people say when they see an icon, and in the recognition wonder if they might have glimpsed her—the real her.