diagrammatic thinking

by Rocco Gangle

Diagrams are concrete structured sets of objects and relations experimented with as such so as to form a kind of laboratory, factory or poem of creative consequence. In working with diagrams, one is at times caught up in a kind of witches’ ride, an at least partially ecstatic transport. This is because when one makes a diagram—and here making is essentially using and testing—one finds oneself transformed into a vehicle or vessel of implicate sense, a sign of all the diagram itself can and perhaps will unfold. Contemporary philosophy has inherited some of its profoundest insights and techniques from diagrammatic thinking. Frege, Husserl, Peirce, Bergson, Deleuze, Guattari, Hintikka, Brandom and many others have used diagrams not only to express their thoughts, but more importantly to produce new kinds of thinking—above all to find new ways to experiment with thinking. One cannot modify or add to a diagram without building and participating in new and unintended relations. Diagrams thus use relations to create and multiply relations.

The logically precise and rigorous aspects of diagrammatic experimentation and expression are not without their spiritual dimensions. A diagram is always a concrete assemblage—a set of scratches, marks, lines and scribbles on a napkin, for instance. Thus the diagram resides in space and time. It is material. But the work of the diagram is to draw immaterial, universal, abstract and atemporal consequences from the relations embodied in the materiality of the diagram itself. The subject who tests, tries, scratches out and revives the diagram is a mediator, a two-way radio, a categorial functor from the micro- to the macro-cosmic. In antiquity, such use of the material world for signaling and explicating the spiritual was called theurgy. In modernity, the diagram stakes out a new consolidation of powers on this old terrain. And it raises the stakes.

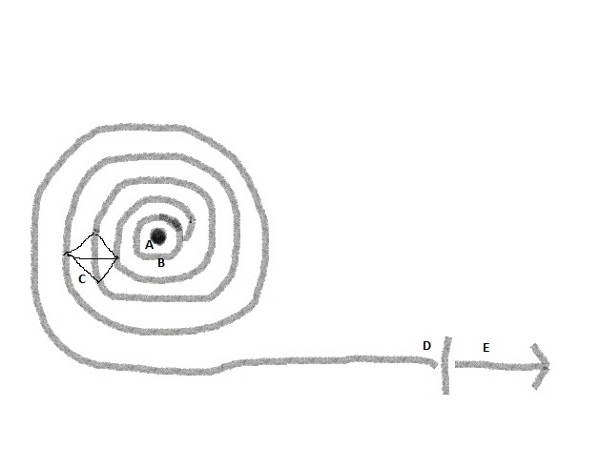

Here by way of illustration we reproduce and adapt a diagram taken from Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus:

As a first step, prior to any interpretation, trace the diagram with your eye or, better, with the tip of your finger. Follow its topology, its flows and cuts, its continua and gaps. Familiarize yourself with its unique territory and note the intrinsic bifurcation and differentiation of that territory into two incommensurable sides—an ACTUAL territory on the one hand, composed of pixels on a screen in front of you, localized in time and space, and a VIRTUAL or abstract territory on the other, delocalized and determined only by internal, structural relations of the diagram’s parts.

Now let us turn to the specific interpretation of the diagram as offered by Deleuze and Guattari. They use this diagram to model the dynamics of signification and of what escapes signification. (Or is it rather that these dynamics themselves in fact model the given diagram? In any case, a diagram is not a formal syntax coordinated to various semantic models; it is a spiritual assemblage, what Deleuze and Guattari call an abstract machine.) Signifying and escaping signification is what a diagram does. Thus the sense of their interpretation and the diagrammatic form of its expression remain strictly inseparable.

We begin by calling attention to certain diagrammatic components: a dot or stain (A) stands at the center of a proximate, centripetal ring (B) while anchoring a centrifugal spiral criss-crossed by leaps and linear relations forming their own micro-systems (C). The spiral terminates finally in a blockage (D) mirrored by or contraposed to an indeterminate jettisoning (E). Having designated these abstract components, we may now examine Deleuze and Guattari’s conceptual mapping. They call the stain (A) the “Center or the Signifier; the faciality of the god or despot.” The ring (B) they name the “Temple or Palace, with priests and bureaucrats.” The relations and micro-systems on the spiral (C) are understood to figure the complex dynamics of signification, with signs “referring to other signs on the same circle or on different circles” which transform “signifier into signified, which then reimparts signifier.” Finally, the blockage (D) represents the “expiatory animal; the blocking of the line of flight,” while the escaping impulse (E) marks the “scapegoat, or the negative sign of the line of flight” (all citations from Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, trans. Brian Massumi, A Thousand Plateaus).

In short, the diagram pictures the transcendental, all-seeing (or all-interpreting) eye that dominates every semiology, every structuralism, every representational venture, and it navigates an escape from the signifier’s tyranny, an emission and no longer a mere interpretation of signs. Such is the very essence of diagrammatic thinking: “The diagrammatic or abstract machine does not function to represent, even something real, but rather constructs a real that is yet to come, a new type of reality.”

In this way, diagrammatic thinking constitutes an imperative, a set of imperatives for lived experience as figured in the spiral and, above all, the arrow of flight in the diagram above: “Destratify, open up to a new function, a diagrammatic function. Let consciousness cease to be its own double, and passion the double of one person for another. Make consciousness an experimentation in life, and passion a field of continuous intensities, an emission of particles-signs. Make the body without organs of consciousness and love. Use love and consciousness to abolish subjectification.”