I once crawled on all fours on an auditorium stage where John Cage sat. That’s an odd confession but an apt image to begin thinking about what we mean by the word “spirituality” or—a more productive task—to begin thinking about which part of speech it is. Is “spirituality” a noun? A verb? Something else?

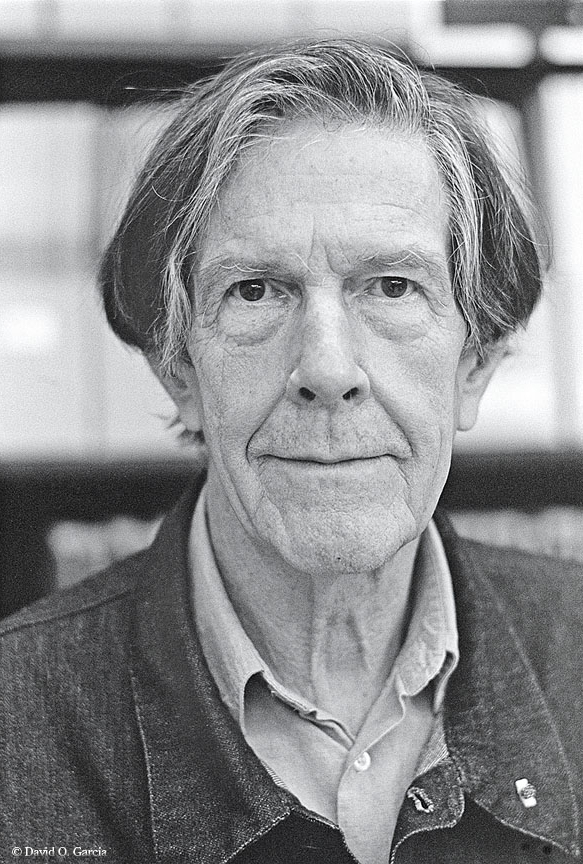

That spring night in 1991 at Miami’s Subtropics Music Festival, Cage had just finished an hour and a half performance of what he called “spoken music.” He had patiently—if guardedly—answered my question about Buddhism’s influence on his work, an issue he’d addressed before in print and at the podium. Yes, he said again, he owed a debt to Buddhism, though he wasn’t sure he’d say he’s Buddhist. After the Q&A that Friday night, three young music students and I—then an assistant professor of religion—asked if we could see the score. In response, the seventy-nine year old Cage quickly and generously dropped it on the stage. The pages fanned out across the smooth surface. As Cage sat nearby on stage after the performance, we then crawled around to reassemble the text and eagerly started reading to learn more about what had just happened in that auditorium.

What had happened prior to my onstage crawling was not immediately clear. Even afterward, some who spent their life thinking about the arts were not sure. The Miami Herald’s experienced music critic James Roos affirmatively answered his own question, “Was Cage putting us on?” The reviewer described how the influential composer had “sat on stage with ‘score’ propped on a music stand, slowly turning pages and drawing unintelligible sounds into a microphone adjusted at mouth level: Ouh … uhh … prawem … pshr … duh-suht.” Then followed, the reporter observed, “several minutes of silence, as the rapt audience waited breathlessly for this next meaningless syllable to emerge: Sipp …utt …pooot …rrrr.” That account also accurately recorded the audience’s response. We heard “isolated interruptions” (including “purposely jangled keys”) and “after an hour or so went by, there were giggles here and there in the audience, mingled with coughs and the shufflings of listeners squirming in their chairs. Little by little, they began exiting…” At the end of my row, a gray-haired man gently elbowed a woman next to him. He then extended his arms with upturned palms to silently pose a question—what’s going on? A few minutes later that couple exited the concert hall in a huff. As they did, she said aloud what many others were thinking: “This is ridiculous.”

Was it? The Herald critic sided with those who had concluded the performance was a “hoax,” but he granted that for some audience members “this Cage ‘concert’ may have been a near-religious new music experience.” The critic’s adjectival phrase (“near-religious”) was interesting since, as Cage had acknowledged, religious texts and practices had shaped his understanding of the arts, including music, dance, poetry, and visual art. As we stage crawlers learned, the performance that night was an excruciatingly slow-paced recitation of a single passage from the writings of Henry David Thoreau, whose work had been a source of inspiration for Cage since 1967.

Even decades earlier Cage had encountered baffled and infuriated audiences, as with those at New York City’s Artist’s Club who attended the performance of his 1949 “Lecture on Nothing.” That piece repeated the rhythmic structure he had used in his innovative musical compositions of the time, including Sonatas and Interludes. It began “I am here.” Then, after the first of many patterned pauses, it continued “and there is nothing to say.” Part of the lecture’s structure came from the repetition—he said it fourteen times—of the refrain “If anyone is sleepy let him go to sleep.” That lecture was not universally embraced, as Cage recalled:

Jeanne Reynal stood up part way through, screamed, and then said, while I continued speaking, ‘John, I dearly love you, but I can’t bear another minute.’ She then walked out. Later, during the question period, I gave one of six previously prepared answers regardless of the question asked. This was a reflection of my engagement in Zen.

Page 1 of 2 | Next page