the walkman

by Ari Y. Kelman

Let me be perfectly frank: I’ve loved each one of the Walkmans that I’ve owned. I even loved my discman and my MiniDisc player, and I’ve loved each of my iPods and now, I love the fact that my cellphone can play music. The invention of mobile music has probably been the most important technological advancement of my lifetime, and it has undoubtedly added a complex layer of mediation between me and the worlds I inhabit.

There are days when I can’t wait to get my headphones in, and other days when everything I choose to hear seems painfully out of tune. There are days when “shuffle” seems cruelly calibrated to chafe against my hearing, and other days when it seems smarter than I am.

Occasionally, I use mobile music as armature, guarding me against a social world I don’t want to get too close to. Often, I use it as accompaniment, to embellish a familiar walk or repetitive task. But always, mobile music is something that’s going to get in between me and wherever I am. Sometimes, it blocks out what’s out there, and sometimes it can invite in what is out there by opening up new ways of hearing spaces, places, and pieces of music that I thought I knew.

I well understand the irony here: my sense of the world around me rests on my ability to import a soundtrack of my own choosing and exert my sonic will on it. There is always another option: to forego my own desires and tune into whatever serendipitous sounds that circumstances generate. In the former, you can hear overtones of ids, egos and control freaks run wild. In the latter, strains of zen-like acceptance of one’s aural environment.

To be sure, an alternative reading of this kind of listening is possible: portable, personalized music echoes with a desire to not hear what everyone else is hearing, to build a sonic buffer from the sensory assault on contemporary landscapes. “If I’m listening to my musical choices,” goes the logic, “then, for a moment, I won’t overhear the overly-loud conversation of my neighbor, or the market-tested, consumer-calibrated, ‘coffee shop’ radio station on the piped-in sound system.” By that logic, not jamming ear buds in your ears is tantamount to sheepishly knuckling under to a world that is almost always under an aural assault (passing cars, car stereos, neighbors fighting, and other sounds you might rather not hear).

To critics, this is nothing but anti-social behavior. Cultural critic Allan Bloom wrote that the Walkman was little more than a distraction from the “great tradition.” Historian of religion Mark Noll described it as “one more competitor to the voice of God.”

Each of these authors uses the aural as a register, but really, they are upset by the broader, social context of the “personal stereo.” Concerns about the Walkman sound like they’re about music, but really, they’re about the culture of listening. The anxiety that the Walkman elicits is that people do not seem to be listening, or that they’re listening to one thing while they ought to be listening to something else. But most importantly, by listening to their headphones, they’re opting out of listening in a more social context.

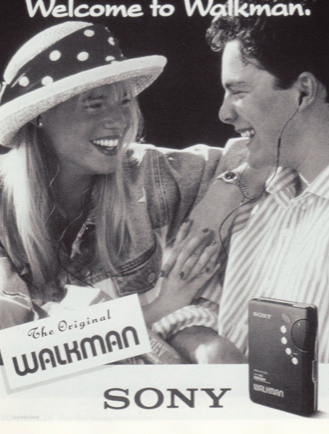

Ironically, the first generation Walkman was supposed to be social. The very first generation of the Walkman had two headphone jacks, and early advertisements featured fit-looking young couples skating and skydiving together, while listening simultaneously, too. The dual headphone jacks represented an engineering response to the possibly apocryphal story of the president of Sony taking an early prototype for an informal test while golfing with friends one day. They all loved the technology but they found it isolating and antisocial.

It’s a strange technical solution to a social problem. If listening seems isolating, let more people wear headphones and listen to the same music simultaneously but separately. The dual headphone jacks were gone by the second generation of Walkman, but debates over the meaning of the Walkman were not.

Recently, in the New York Times, sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh blamed iPods for keeping Americans from rising up in protest about America’s recent economic turmoil. “In public spaces,” he wrote, “serendipitous interaction is needed to create the ‘mob mentality.’ Most iPod-like devices separate citizens from one another; you can’t join someone in a movement if you can’t hear the participants.”

We can again hear strains that the Walkman (or its more robust technological offspring) inhibits social interaction, impedes participation in civic life, and otherwise distracts people from paying attention to something more important than their favorite song. Cultural Studies scholar Rey Chow has written that this kind of “distracted listening” represents a political statement, of sorts, a refusal to participate in mainstream sonic-social discourse.

I disagree. Chow misses the fact that both the music and the technology on which it relies are embedded in other circuits of capital and power, thus making it impossible to be fully distracted—you are always “hearing” the technology as noise in the cultural circuit. If the technology itself were mute, then listening to a Walkman would be the same as listening to anything else (a portable stereo, a transistor radio, a loudspeaker).

It’s not. Listening to a Walkman is a particular kind of listening, and listening to an iPod is yet another. It is perfectly postmodern, insofar as this kind of listening always calls attention to the material condition of the act of listening itself (this is why Apple’s white earbuds were such a brilliant advertising move). Similarly, the Walkman is a beautiful artifact of late liberal culture, with its emphasis on individual choice and fulfillment; with my Walkman, I only need to hear what I want to hear, provided I’ve paid for it.

Yet, the beauty of the Walkman, further elaborated by the iPod, is that it is often mobilized as a refusal of those same cultural contexts. Every act of listening performs tensions between what one hears and how one hears it, between where one is and what one is attending to, between what one wants to hear (my music) and what one hears (the technology), between connecting with my environment and being distanced from it, with little or no hope for reconciliation.

Nevertheless, I keep listening, and perhaps those tensions keep me listening, so that I might hear a little better the spaces between the notes, the pauses between the words, the gaps between what I hear and how I hear it.