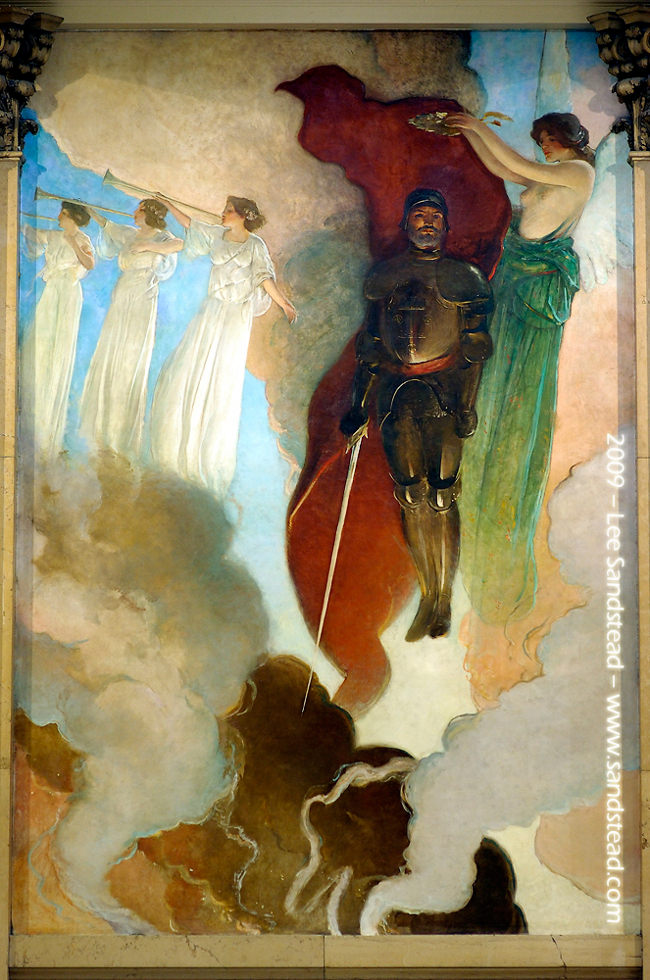

Sanctifying those who govern, harnessing official religion for state ends, inspiring the people, channeling their dreams—even in modernity angels adorn public structures and monuments, whether in victory pillars, war memorials, or paintings of the apotheosis or heavenly ascension of great leaders. The Apotheosis of Pittsburgh, by the then-renowned American artist John White Alexander, is a series of 48 murals, all painted by Alexander between 1905 and 1915, in the grand staircase of the Carnegie Institute (now the Carnegie Art Museum) in Pittsburgh, a cultural haven sponsored by industrialist Andrew Carnegie, dedicated in 1895. Alexander died in 1915, leaving his enormous mural cycle unfinished. The paintings tell and glorify the story of the building of Pittsburgh through the kinds of industries that Carnegie ran and that made him wealthy enough to found institutions for the people devoted to culture and the arts. In the 2nd-story painting known also as The Crowning of Pittsburgh, a knight in black armor floats heavenward, to the sounding of trumpets, about to be crowned with a wreath by angels, the man who made all this bounding development possible, the hero. The knight is meant to be a virile personification of the city of steel and looks quite similar to the Institute’s benefactor, Andrew Carnegie.

Alexander meant his monumental artistic feat to instill in viewers a historical yet mythological narrative that made American industrial capitalism a manner of fulfilling God’s purpose. I came across images of Alexander’s angels while researching a forthcoming book on angels and modernity. As with so many modern angels, I find these riveting. Despite the supposedly anti-metaphysical bent of modernity, the art of public spaces continues to aspire to shape people’s spiritual dreams. Hence one explanation for the continued ubiquity of angels.

Around the ascending knight/Carnegie, around across some of the walls of this enormous “grand staircase” flits a bevy of gorgeous angels, slim, vanilla pure and elongated, an art-nouveau-like chorus line, adoring fans, coming forward with gifts. Their garb resembles fancy evening dresses, their faces and expressions not un-innocent. A few of the winged beauties in the foreground—therefore the largest, most prominent, also highlighted because unlike others they wear colored outfits—are topless, their breasts detailed in a way rather risqué for the angelological tradition. This makes an interesting choice for Alexander, whose many portraits of (human) women, though dwelling attentively on femininity and sensual detail, never depict anything immodest. The figures in The Apotheosis of Pittsburgh are not technically angels. Because the painting hails from a classical genre (apotheosis), they are actually winged genies from classical mythology, not Judeo-Christian angels. The different winged beings from different cultures have a history of coming together and interbreeding, however. Most of the artistically-aspiring viewers of Alexander’s paintings would have understandably seen these winged females as angels. The rising black knight, the modernity of all of the scenes of the building of Pittsburgh serve to Christianize the cycle and essentially make these attractive fairies into angels.

Page 1 of 3 | Next page