family tree

by Eric Scott

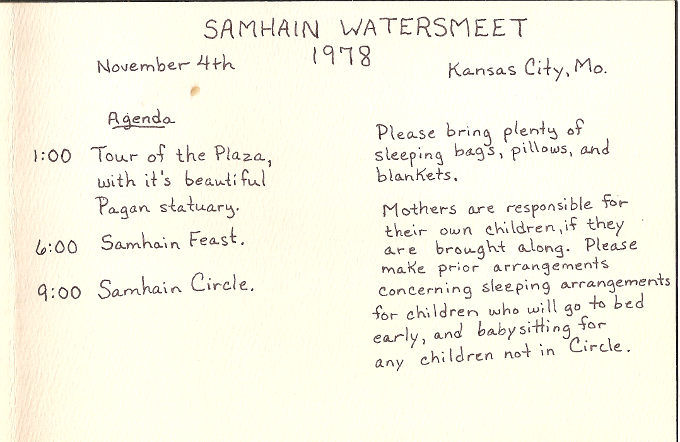

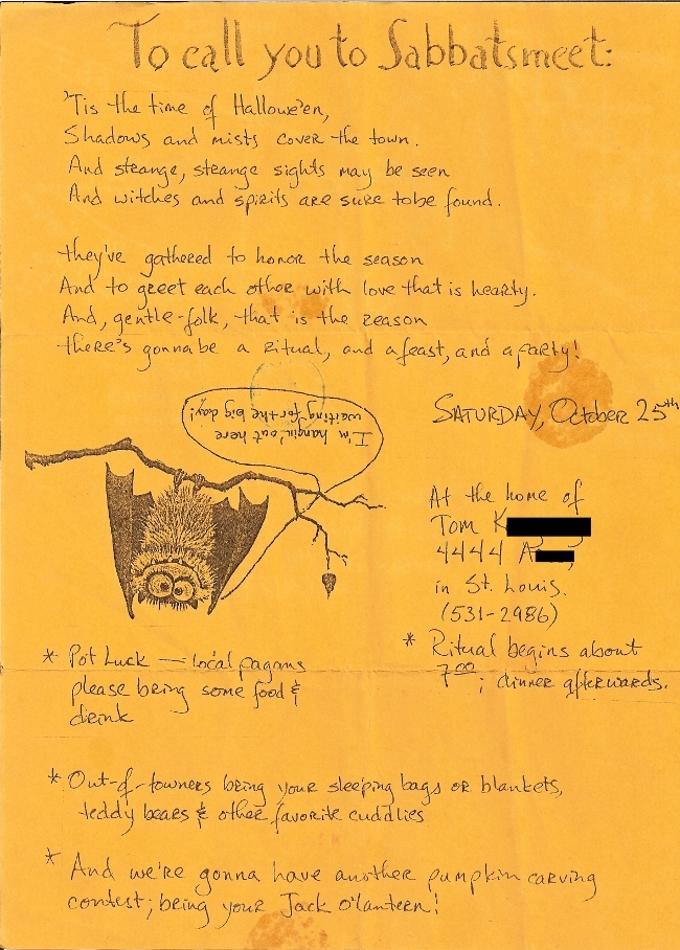

This card—hand-lettered and never-sent—is the earliest document of my family tree: an invitation to a party held a decade before I was born. It’s the only thing I’ve ever seen that’s old enough to bear the name our immigrant parents gave us, Watersmeet. It should not seem so old, but it does; this card from 1978 has the weight of a great-grandmother’s lost pearls, and though it hasn’t even yellowed with age, my mind conjures the dusty scent of memory when I hold it between my fingers.

I asked my father about Watersmeet. “I don’t know, son,” he said. “That was all before my time.” He joined the coven in 1983, only five years later; how could things have been forgotten so quickly? But in those five years, we’d lost Carrie and Deryk, those British wanderers who had brought us word of Wicca from the old country, who had left, gone away to Oklahoma and Iraq, to building plans and brain tumors, to fates none of my family seem to know. In just five years, the family had fractured, from one coven between the Mississippi, Missouri, and Meramec—St. Louis, where the waters meet—to covens across the Midwest, in Kansas City, in Des Moines, in Springfield. By the time my parents joined, they called it Sabbatsmeet, the name I’ve known our family by since before I knew what religion meant.

I found the card in a collection of invitations my friend Sarah kept, invitations that told the history of Sabbatsmeet in six-week intervals. Eight festivals a year, each one of them heralded by a letter with a time, a place and a picture. They’re about the only letters I get anymore. Sometimes they feel anachronistic—Why do we keep a mailing list anymore? Hasn’t everyone had email for a decade?—but we send them anyway, to people who already know about it from the Facebook group, to people in Alabama and California who haven’t made it to a sabbat in decades. I looked through this folder, at these pages of Commodore 64 typefaces and hand-drawn directions, hoping that somewhere in there I’d find my own history—whatever that is, whatever that means.

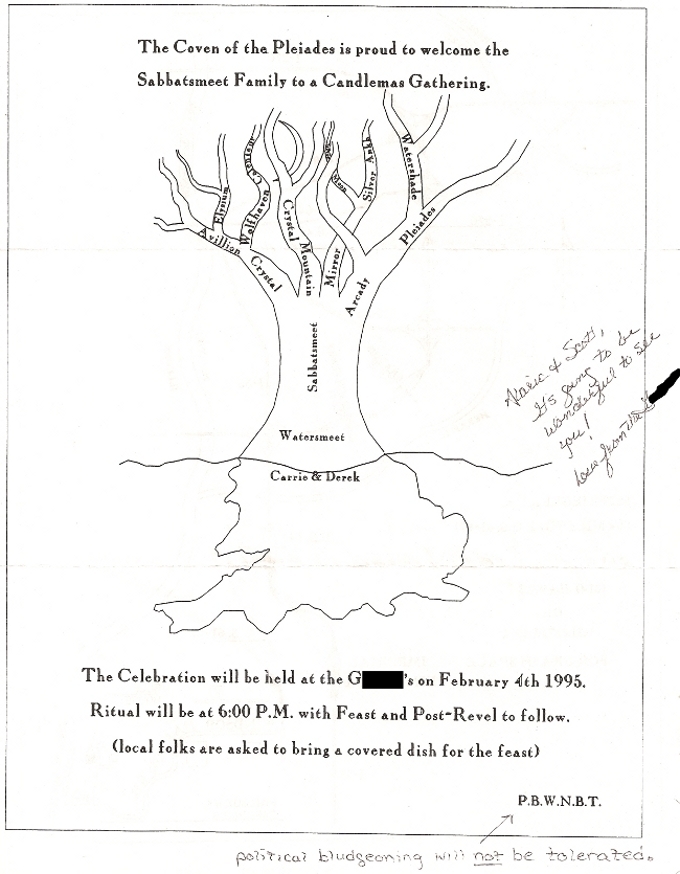

Look at this tree.

I understand the rightmost branch, the St. Louis covens: Pleiades—that’s the coven I was born into—and next to it, Watershade, our sister. (In the decade and a half since this was drawn, there has been another branch, HollyOak, already come and gone.) They grew out of Arcady, which came from Watersmeet. This much I knew, if only from osmosis. But what about the rest? Silver Ankh? Crystal Mountain? Elysium? Why have I never heard of these?

Sarah fills in some of their stories. “Avillion, I think that was Rhiannon’s group,” she says. “And Elysium’s still around. Lane and Cheryl.” The left-most branches are all the Kansas City covens, whom we lost touch with after a hard divorce. It takes a phone call to Don, once the priest of Arcady Coven before he left Missouri for Florida, to learn much of anything about the others. He told me stories of Deryk and Carrie, he with his bushy mustache and his dry wit, her with her bright red hair and poor coordination: “She was our ‘Aunt Clara,’” he says—the clumsy aunt on Bewitched. A week before a Mabon festival, Don and his wife Alene had stopped by Carrie and Deryk’s to find them packing their suitcases. “We have to move to Kansas City for Deryk’s work,” they told him. “Now you’re the priest and priestess.” The next Beltane—the first of May, when we dance with ribbons in hand and twine ourselves around the Maypole—he’d said they should stop calling themselves Watersmeet, since their meetings weren’t about one coven anymore, and how some new girl from Duluth had said they should call it Sabbatsmeet instead…

I smiled when I heard that story. Elaine, Sarah’s mother, is as close to me as any aunt; once, she’d just been some girl from Duluth. She would have been younger then than I am now. Somehow that seems impossible—not that she could have ever been that young, but that she could have been a part of Sabbatsmeet at that age, could have named it. It feels like it should have always belonged to people older and wiser than me. But it didn’t. They were just kids at the time.

In my head, I know that. I still can’t believe it.

A coven is not a church; there are no buildings, no pastors with divinity degrees, no Women’s Group postings on the bulletin board; only my parents’ living room on a Friday night, the coffee table filled with athames (wiccan ceremonial knives) and chalices and candles. Ultimately, there is nothing material to hold the enterprise together—nothing but the will of its members. That’s all fine: when it works, it’s full of intimacy and love, a good place to grow up in.

But it doesn’t always work. Sometimes people disappear—they move away, or they get divorced, or a friendship ends violently—and they take their memories with them. A few things get saved—some records of the early days, some lists of names unspoken for decades—but it seems like so much more has been lost, stolen away by changes of address and wounds that never had a reason to heal.

I’ve learned things I never even knew to ask about by leafing through this folder—a history that I didn’t know existed. Mostly it makes me wonder how much more there is to find, how many more people I owe some of myself to. I want to know my people, my parents, what their lives were like before I was born. Working-class Missourians like my parents were probably not the people Gerald Gardner and Alex Sanders would have expected to reach. But somehow their religion did, passing from England, with love from Deryk and Carrie, through Watersmeet, through Sabbatsmeet, through Pleiades, through my parents, to me. It just seems so improbable—but it happened. How?

I heard that Tom, the one who sent the Samhain invitation with the grinning bat, went into the hospital last week. Liver failure. It doesn’t seem right that a man who would remind his friends to bring their “teddy bears & other favorite cuddlies” should be vulnerable to that. But people are fragile, and too easy to lose. Sometimes the invitations outlast the parties.